What Do I Tell My Children?

How to flourish as a human in the age of AI

Welcome to this special update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 30,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

Hi Everyone,

It’s been a little quiet around here recently, but that’s all about to change.

And to get us started, here’s an essay of mine that I think will be right up your street. This essay was published in The Exponentialist, the technology-focused research service I founded with Raoul Pal. It went to those readers a while back, and it really struck a chord; it’s still one of the essays I get asked about most often. The ideas in it remain deeply relevant as 2026 gets underway.

This piece is called What Do I Tell My Children? It’s about navigating the wildly new future that intelligent machines are building around us.

Enjoy!

Introduction

My working life consists of lots of research and a ton of writing. That’s the part you see here in The Exponentialist.

But in addition to that, for years now I’ve done a lot of public speaking. The year just passed was no different. Among others, I went to speak to the C-suite of a UK-based challenger bank. To the C-suite of a high street health and wellness retailer. And to the marketing team at a global media network.

And they all had one request: talk to us about AI.

That was no surprise; it’s been this way for the last three years or so, ever since the ChatGPT moment. Every business is struggling with the same questions: what does AI mean for us? How can our people put it to work? How will it change our customers?

These are the questions I address when I speak.

But at the end of these talks the same thing happens; almost infallibly. I take some questions, and then there’s a pause. Amid the silence, someone will tentatively raise their hand, as though they are unsure whether they’re allowed to do what they are doing. And then they’ll say something like this:

‘That was all very interesting. But having listened to your vision of what is coming, I’m deeply worried.

I’m the parent of an eight-year-old girl and an eleven-year-old boy. My head is spinning on what this world is going to mean for them. If AI is going to be as powerful as you say, if it’s going to do so much of the work currently done by humans, if AIs are going to start businesses, and discover new scientific theories, and run financial markets, what role does this leave for my children? What kind of career are they going to pursue? What kind of life can they build? What am I supposed to tell them?’

Across the last 20 talks I’ve given, I’ve got some version of this question almost every time.

That’s totally understandable. I know firsthand: once you have an inkling of the vast changes that are coming, then as a parent it’s impossible not to have deep concerns.

And, of course, you don’t have to be a parent to be worried about these issues. The AI revolution is unfolding at lightspeed; if you plan to be alive ten years from now, then it’s going to have a profound effect on your working life, too. You’ll be asking: where is all this going? How will it affect me? What can I do to prepare?

Many of us are old enough to remember — just about — a form of working life and attendant social conditions that have now passed into history. I mean the form of life that is latent in a picture such as this:

We all know what a picture such as this signifies.

That is, the age of the prosperous middle class existence built on one ordinary salary. The corporate job for life; one in which ageing middle managers were not booted out as soon as they stopped being productive, but instead eased respectfully towards retirement in their early 60s. A retirement, by the way, funded by a generous pension that would allow them to maintain their standard of living.

That world, as we all know, is already long gone.

But what fewer people understand is that change is coming that will make that transformation look small indeed. Pretty soon, the working lives and attendant social conditions that exist now will seem as archaic as those in the picture above. And that will be just the start.

Nevertheless, I am fundamentally optimistic about what is coming.

We humans are fantastically adaptable. Each of us is a wellspring of infinite, insatiable wanting. And there are many things we’ll always want from each other. These three truths will form the basis of a new kind of economy. Yes, it will be an economy that is changed beyond all recognition — one we’d barely recognise as an economy now. But even in that new world, there will be many ways for humans to create and exchange value with one another.

So there will still be opportunities for your children — and your future self — to carve out a meaningful working life, and to build a wider life of joy and purpose. It will just all look much different to the typical careers, and routes through life, that we’ve lived through across the last 30 years or so.

In this essay, I want to go deeper on how I see all this playing out.

So this is my first properly codified, longform answer to the question I’m asked most often by the senior professionals I speak to: what do I tell my children? Remember if you have no children, the principles I’m about to lay out will still be deeply useful to you. Either for when you do become a parent, or as you plan the next five, ten, or 20 years of your life.

I’ve cultivated seven core principles to help prepare children for the coming Exponential Age.

But before I dive into them, I want to take a minute to define the challenge those principles address. That is, to define the set of conditions that I believe is coming.

The Coming Economic Singularity

We’re talking, in this essay, about how to prepare our children for what lies ahead with AI. So before we get into how to do that, we need to be sure we have some shared sense of a prior question: what, exactly, lies ahead?

After many essays, we’re all steeped in Exponential Age thinking. So I’ll keep this brief — a reminder of the AI-fuelled world that I have been writing about here for two years and more.

One glimpse of the world that is coming? Look at the results people are achieving with Claude Code. Look back, even, to OpenAI’s o3 model, released in December 2024. It can solve problems included in the Frontier Math Benchmark, a test designed to test AI models against the bleeding edge of mathematics. These are problems so hard that no ordinary person can come close to understanding them, let alone offering a solution.

In short, it seems likely now that we’re at the foothills of superintelligence — and something we can meaningfully call AGI — within the next five years. Perhaps far sooner.

What does that world look like? For our purposes, three major pieces of the puzzle are relevant:

AI is capable of performing 99% of the cognitive and knowledge work currently performed by people. We have near-infinite, superhuman knowledge workers.

AI is at the intellectual frontier. It is making new discoveries in science, maths, engineering, and tech, and transforming our view of the world around us. But we are struggling to understand much of what AI is uncovering.

AI can converse like a person (this has pretty much happened already) and autonomously perform complex and longrange tasks. Billions of people run their lives through an AI virtual companion that knows all about their tastes, preferences, and lifestyle.

I’ve written about a coming Economic Singularity. These three realities will form a key part of it. They will fuel change so vast it is hard for us, now, to envision what lies on the other side.

AIs will build startups in a day, launch tokens, take profits, and disappear. AIs will transact with other AIs. Big corporations — Accenture, Unilever, Disney and the like — will have vastly reduced need for human knowledge workers and creative talent. It goes on and on.

At some point — and this could happen quite suddenly — we’ll wake into a world in which all the old models and frameworks we’ve to make sense of the economy simply no longer function. We won’t exist in anything we currently recognise as an economy.

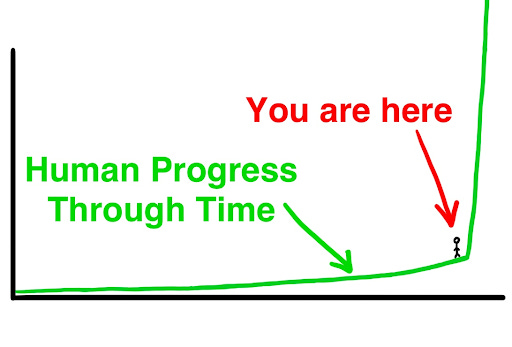

This famous image from Wait But Why captures something of the essence of what we’re talking about:

This is the vision that so worries the professionals I speak to.

It is a vision of a world utterly changed — in all kinds of ways. But when these professionals raise their hand and ask about the implications of all this for their children, it’s the career and economic implications specifically that they are asking about. The seven principles I’m about to lay out, then, focus on that. But everything, of course, impacts everything else, so via my seven principles I’ll also touch on broader social and personal implications of what lies ahead.

Okay, we’ve laid sufficient groundwork. Let’s get into it.

Designs for Life

Yes, vast change is coming. But amid it all, we can still help to prepare our children and our future selves.

Put these principles into action, and I believe you’ll build skills, behaviours, and attitudes that will empower your child to flourish in the new world that is coming.

The principles, of course, cannot be foolproof or comprehensive. They are my best early attempts to address a challenge that is in its early days, and evolving fast. I try to apply them as best I can as I raise my own children — twin 11-year-old boys — here in the UK.

I’ll lay out the principles one by one, and along the way we’ll develop a picture of the world I believe is coming.

Given the people I speak to and the nature of our economy, these principles are weighted somewhat towards parents who imagine a knowledge work future for their children. Many argue that in a world of AI, manual tasks — think gardening, or plumbing, or physical therapies — will skyrocket in value. There may be some truth in that in the short term. But given the pace at which humanoid robots are advancing it seems to me that the future of gardeners is also not clear.

So I’ve tried to develop principles that can provide a foundation to build on, whichever direction your child takes in the end.

1. Build your child a surfboard

This one is simple, but deserves some space.

At the deepest level, the challenges our children will deal with as they hit the labour market are twofold. They are lightspeed change fuelled by technology, and attendant deep uncertainty.

AI will be transforming the economy. No one will fully understand what is happening. No one will know how it is all going to turn out. In this environment, our children will need to draw on immense reserves of adaptability and resilience. So we need to cultivate those virtues now. This is the most common advice given when it comes to how to prepare children for the age of AI. But it’s true.

In the old economy, we told children to develop one set of professional skills and expertise — in law, say, or medicine — and then to deploy those skills and expect a secure career as a result. In the world that’s coming — in which AI does the work of millions of lawyers, doctors, consultants, and more — that route will be available to very few.

Instead, far more knowledge and creative workers will be independent or freelance, seeking their own opportunities, moving from project to project. And wave after wave of technological and social change will continue to disrupt the ways in which those workers can bring value to others.

So those workers will need to be able to shapeshift, to spot ways to deliver value, to create opportunities for themselves, and to rapidly learn the skills needed to deliver.

Think of the old economy as a bit like driving a car. You learn to drive once, and then you set off down the road. You get a better car every so often, so as you go you can drive faster. But fundamentally, you’re driving down the same kind of road and it will carry you to the end of the journey.

The new economy will be much more like surfing. Opportunities will rise and fall like waves (I’ll say more later on what those opportunities will look like). You’ll need the ability to spot a wave when it is coming, to discern its nature, and then — if it’s the right wave for you — to ride it. You can’t know in advance when a wave will come, or what it will be like. You need to be flexible, and ready to ride.

So how do we cultivate this kind of flexibility and resilience in children?

Part of the answer lies in very familiar parenting advice. Build emotional security in and around your child, such that they feel they have permission to take an exploratory view of life: to experiment, fail, and try again (more on failure later). I know what you’re thinking: every parent strives to build these foundations — it’s easier said than done. But in the new economy that’s coming, these virtues will be crucial.

A more straightforward tactic: talk to your children often about the kind of working lives I’m outlining here, and the age of AI more broadly. Make them understand that the kind of single-track careers they see on TV or hear about in school — the kind that many of us have had — aren’t really going to exist in the future they’re heading into.

I talk to my children a lot about my existence as an independent researcher and writer on technology, surfing the waves I find, and building my own opportunities. Not (only) because I like to Bore Them Into Submission With Stories About Dad, but because I think it’s highly likely that they’ll have a similar kind of independent, wave-surfing working life.

Think of all this as building a surfboard for your child.

Fundamental to the kind of adaptability our children will need is the ability and appetite to always be learning. Surfing the waves that rise and fall will mean rapidly learning new skills.

And on that front…

Working for Singularity University itself a decade ago, and monitoring a lot of technological and social changes and upheavals since then, I've come to a very different set of conclusions about human progress than Tim Urban's Wait But Why.

I've perhaps fallen more into the John Gray than Steven Pinker camp on this one. But everywhere I've observed so-called "abundance", I've witnessed scarcity merely shifting somewhere else or changing form. Every time I've been tempted to believe in an ever-accumulating knowledge and wisdom of our species, I've discovered more and more concrete examples of how so-called "primitive" societies knew things that modern man has completely forgotten and is clueless to remember today.

Which isn't to say I'm a doomer. I'm just more of a finite systems thinker. One who believes we forget, often intentionally, at least as much as we learn. How our minds atrophy in a kind of biological garbage collection so that our dendrites might be consumed instead by the new fads of a new time. Human progress thus becomes more a rearranging of the furniture than some grand capitalistic orgy of infinite exponential expansion.

I do like the surfboard analogy, as it relinquishes greater control to forces beyond ourselves and requires us to work within their larger energy waves. But cognitive debt is pretty much a requirement for our broader social adoption of AI in any meaningful way, for example. Children need to learn the value of unlearning.

Bookmarked. Thanks for your valuable article! Lots of ah-ah moments. 😊 🙏