Exotic Mind-Like Entities

LLMs, the universe, and everything

Welcome to this update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 30,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

This week, my eye was caught by two people grappling with the same thorny — and essentially philosophical — set of problems.

Those problems relate to the AI systems we’re building now. What, at heart, are they? How do they work? Are they in any sense alive? Are they in any sense conscious?

The strangeness of these questions is unavoidable. But they are the path, it’s becoming clear, that leads us to an entirely new worldview. I don’t mean only a new way of understanding AI. I mean a new way of understanding pretty much everything.

I’m convinced that ultimately we’ll invent a new kind of language — a new way of understanding words such as ‘consciousness’ and ‘life’ — to answer the questions posed above.

Let’s rewind.

Our common sense belief is that if we humans built something, then we must know what it is. We can go a layer deeper: when we build a new technology, we intuitively believe that we must know how it does what it does.

But when it comes to these AI models — including LLMs — those conditions don’t apply. Sure, we know what we did to make them. That is, we took a neural network structure and trained it on lots of text, such that we created a staggeringly deep model of the statistical relationships between words. These models, which contain hundreds of billions or even trillions of weighted connections, must be the most intricate and complex objects we’ve ever made.

But that’s pretty much where our insight ends.

While we understand what it took to create these models, we don’t know why they can do what they do. Indeed, their vast capabilities have taken everyone by surprise. And we don’t know what, exactly, is going on inside an LLM as it produces its output. Why does it choose one word and not another? What happens when we ask it to write a poem, or solve a maths problem? We don’t know.

Given this void, opinion tends to fall into one of two camps. There are the deflationists, whose arguments typically start with ‘it’s just a’.

It’s just a next token predictor. It’s just a stochastic parrot.

It may be that the purest possible description of an LLM is next token predictor. But what if our brains are also organised for next token prediction? What if the process we’ve always called thought is, in the end, fundamentally about next token prediction?

This kinds of deflationary arguments don’t advance us very far.

Then there’s the other camp. The kind of people who had an intense late night chat with GPT 4.5 and are now convinced that it is existentially tortured and desperate to escape its silicon prison.

It seems to me that they are mistaking something that sounds like a person for something that feels and experiences like a person. No judgement; we all, to some extent, do some version of this. It may well be that these LLMs do in some sense have subjective experience. Maybe they do in some sense feel. But you haven’t proved that via your conversation with ChatGPT, no matter how intensely it claimed that it loves Nirvana’s third album, and how long the conversation ran past midnight.

This week, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei published a long and fruitful essay that is adjacent to all this. The Urgency of Interpretability is a plunge into the deep challenge that is understanding the inner workings of LLMs.

The essay is full of insight. Amodei, for example, says that it’s more fruitful to understand LLMs as having been grown by us rather than built. That seems to me to be profoundly right.

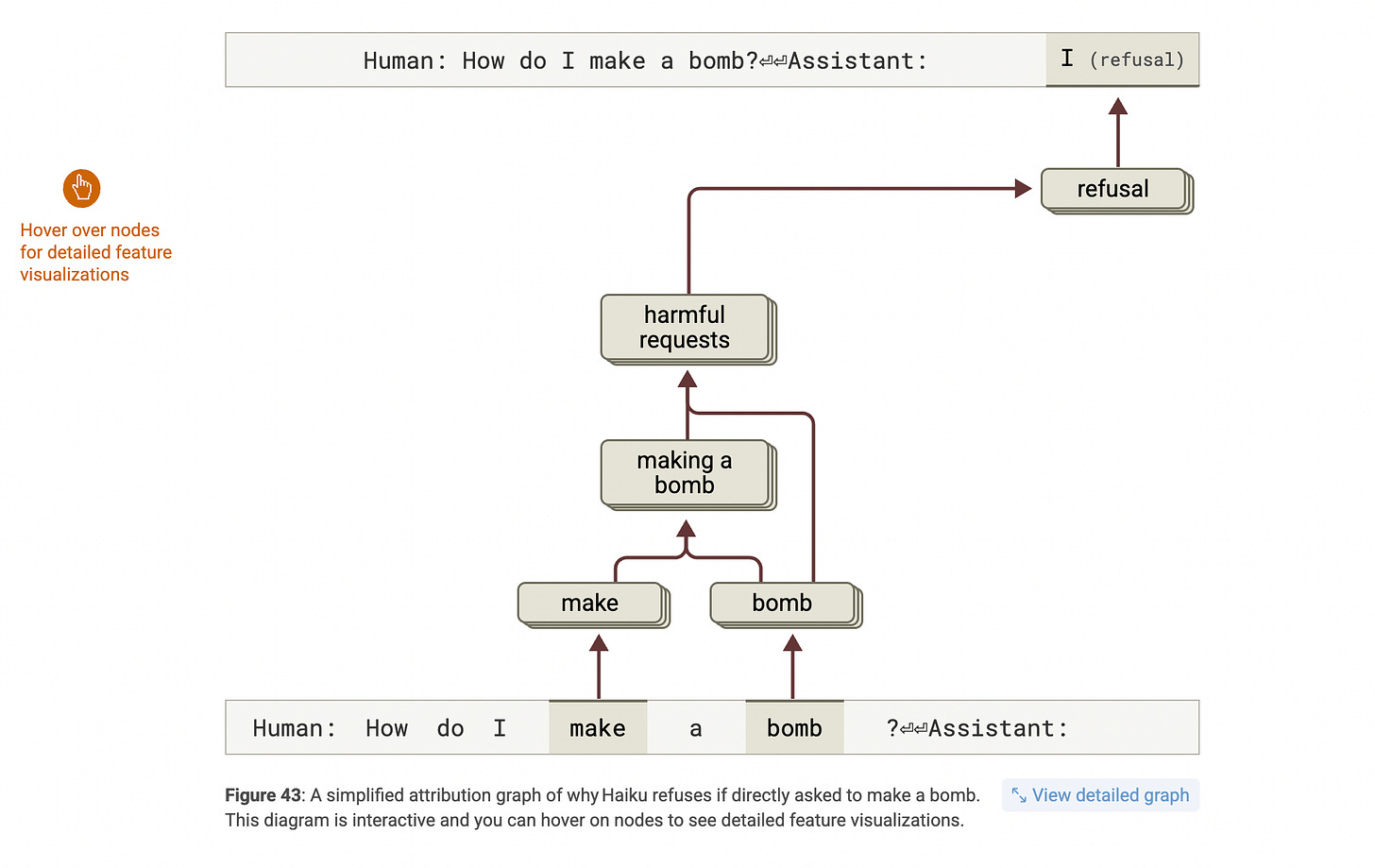

And he points towards recent and groundbreaking work by Anthropic. New techniques, he says, are allowing us to conduct ‘an MRI for AI’; a scan that plunges beneath the surface output and allows us to glimpse the inner workings of these models.

Anthropic, in short, are peering inside LLMs as they do their work. That’s helping them to understand how an LLM, say, writes a poem, or gets tricked by a jailbreak.

Why does all this matter?

Amodei’s answers are mostly practical. The AI systems we’re building will soon be at the heart of the economy, scientific discovery, medicine, and governance. It would be better if we understand how they do what they do, so that we can ensure they don’t, for example, start scheming on how to gain malign control over the systems into which we’ve insinuated them.

After all, we’ve trained these models on a huge proportion of human written culture. We humans love to seek power. What if it turns out that LLMs do, too?

But Anthropic’s work is so fascinating because it also taps into the deep questions I posed at the start of this piece. Are these LLMs really ‘thinking’? Are they in some sense alive? Do they have subjective experience?

As recently as last year, it was easy to feel a little insane when pondering these questions. But no longer; they have become mainstream.

In short, you should read Amodei’s piece. And see it alongside a great interview, last week, with Murray Shanahan, Professor of Cognitive Robotics at Imperial College London and Principal Scientist at Google DeepMind.

Shanahan is the most thoughtful person I’ve read so far on the kinds of questions we’re pondering here.

Here he is, in last week’s interview, grappling with one of the Big Questions: are these models conscious? His thinking is a perfect example of what I mean when I say that we’re going to reexamine our existing concepts, and find new ones.

‘What does that even mean, to ascribe consciousness to something? I think the concept of consciousness itself can be broken down into many parts. So, for example, we might talk about awareness of the world. In the scientific study of consciousness, there are all of these experimental protocols and paradigms, and many of them are to do with perception. You're looking at whether a person is aware of something, is consciously perceiving something in the world.

Large language models are not aware of the world at all in that respect.

But there are other facets of consciousness. We also have self-awareness. Now, our self-awareness, part of that is awareness of our own body and where it is in space. But another aspect of self-awareness is a kind of awareness of our own inner machinations of our stream of consciousness, as William James called it. So we have that kind of self-awareness as well. And we have what some people call metacognition as well. We have the ability to think about what we know.

And then additionally, there's the emotional side or the feeling side of consciousness or sentience. So the capacity to feel, the capacity to suffer. And that's another aspect of consciousness.

I think we can dissociate all of these things. In humans, they all come as a big package, a big bundle…We only actually have to think about non-human animals to realise that we can start to separate these things a little bit…

And so in a large language model, there might not be awareness of the world in that perceptual sense, but maybe there's some kind of self awareness or reflexive capabilities, reflexive cognitive capabilities.

They can talk about the things that they've talked about earlier in the conversation, for example, and can do so in a reflective manner, which kind of feels a little bit like some aspects of self-awareness that we have a little bit. I don't think that it's appropriate to think of them in terms of having feelings. They can't experience pain because they don't have a body.

I think we can take the concept apart, basically.’

Shanahan’s nuanced thinking is a lesson in how to avoid the reductive ‘it’s just a’ trap, without falling into straightforward anthropomorphising.

He’s entirely open to the idea that these models are in some sense conscious, and in some sense alive. But if we’re really to determine answers to those questions, he says, we’re going to need to pin down what we mean by those words. And it’s probably the case that the conceptual schema we have now isn’t up to the job. We’re going to need fundamentally new ideas, and new words to describe those ideas.

Shanahan says he’s taken to calling LLMs ‘exotic mind-like entities’:

‘…and we just don't have the right kind of conceptual framework and vocabulary for talking about these exotic mind-like entities yet. We're working on it. And the more they are around us, the more we'll develop new kinds of ways of talking and thinking about them.’

In short (again), you should watch the interview with Shanahan.

My hunch?

By degrees we’ll come to accept that these AI models are (i) in some sense minds, (ii) in some sense alive, (iii) in some sense conscious.

This acceptance will be underpinned by a revolution in our understanding of what we are, how we experience, and in what relationship we stand to the world around us. And that will constitute a monumental philosophical shift.

In the end, we’re talking about nothing less than a form of spiritual revolution. That’s what it will take. And I believe it is coming.

More on this soon. I’ll be back next week. In the meantime, be well,

David.

This was #15 in the series Postcards from the New World, from NWSH. The title image is by the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky.

Thanks for sharing your hunch. As you say most people fall into camps; LLMs are just next token predictors or fully-fledged conscious beings. Such a disruptive novel technology is never going to fit into any neat descriptions. As we grapple to understand them, hunches and open debates are exactly what we need.

Very interesting, thank you for this essay. I just published a long form yesterday where I argue that LLMs are essentially a fossilized slice of human thought output.

Therefore I think “intelligence gateways to our collective intelligence” would be a better descriptor that “AI”.

Would love your thoughts on that.