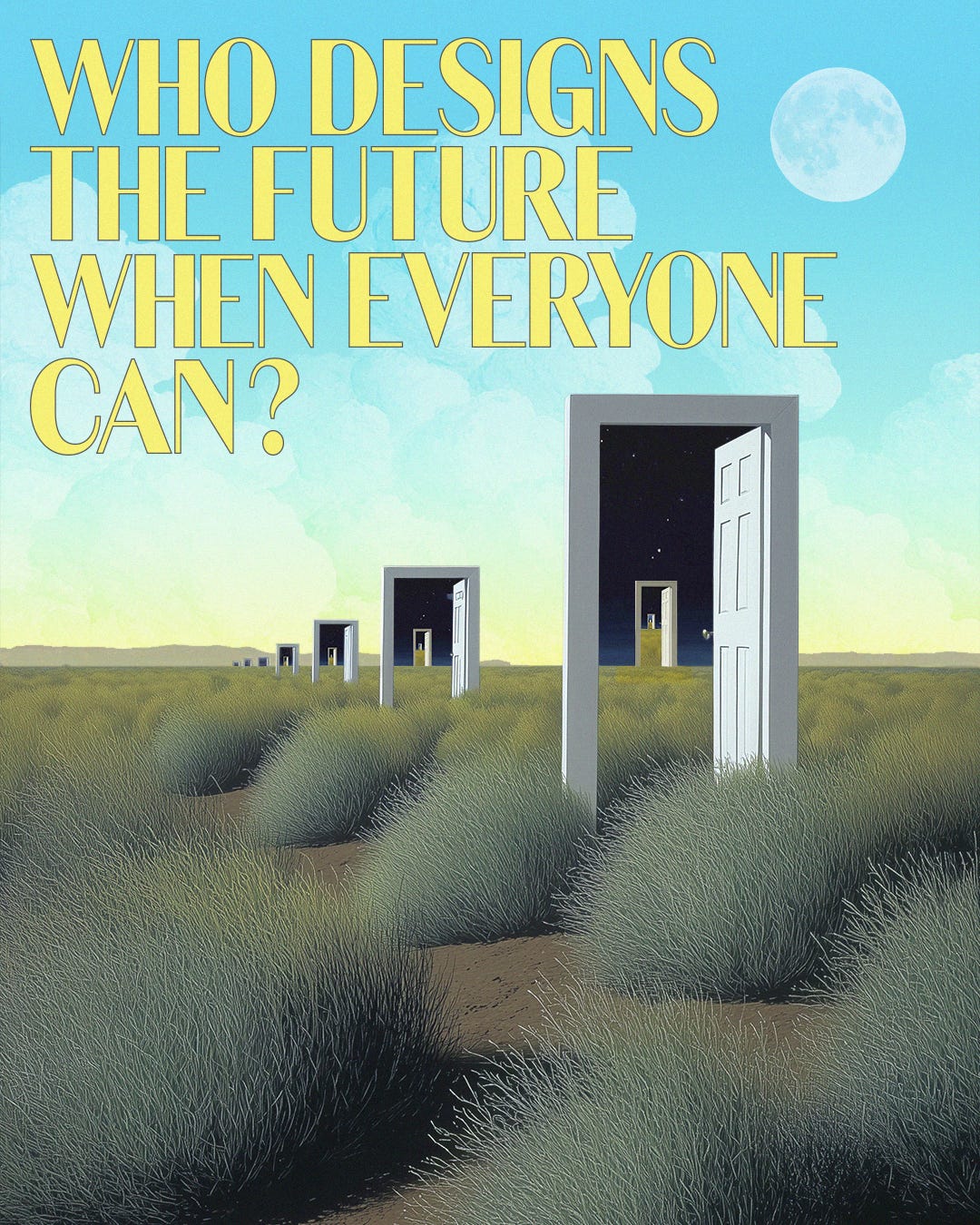

Who Designs the Future When Everyone Can?

A new essay from Full Moon

A few days ago over at Full Moon, we published our second deep dive essay. It’s called Who Designs the Future When Everyone Can?

In this brilliant piece my Full Moon co-founder Mark Curtis goes deep on the present and future of design. If you're on a quest to make products, services, campaigns and more that people love in 2026, you need to read this.

To jump straight to the full piece, just hit the button:

The full essay is for paid members. But you can read a preview of it below. If it resonates, just click through to sign and keep reading.

Remember, subscribers to Full Moon get a monthly deep dive essay, as well as a monthly podcast, regular live Q&As with me and Mark, and the weekly Ideas newsletter. They can also choose someone aged 28 or under to receive one year’s complimentary membership.

Without further preamble, then, here is that preview. Over to Mark…

Introduction

AI is a game changer for how we conceive of, create, and sell products and services, whether we like it or not. That’s because it makes everyone a designer.

This massively affects how we are going to make great things we love in the next 10 years. And what we will then experience as humans.

I am going to unpack three big issues – who will make winning experiences, what they will make and why will we care. This is all about how you get to be different in the age of AI.

It is already way easier than ever to start a business, to create experiences. Yet power is concentrating in the hands of a few giant tech companies. How will those two statements balance out? Sheer levels of competition to make things, and deliver great experiences will be insane, chaotic.

So how do you get to great and stand out? Winners will have a clear intent behind what they make – difference will matter more than ever, delivered through a clear mission and the highest possible product quality.

The design of AI output itself is still in its infancy. We often imagine we are at maturity years before it actually arrives – we have a long way to go and the key to unlock this is asking: is any manifestation of AI a product or a feature? Trust and taste will be critical.

And last, humanity needs to be at the centre – not just of the whole AI project but each successful manifestation. Authenticity will command a premium, and that depends on humans being able to find a back story, satisfy themselves it is real, and revel in the delight of the new.

Let’s dive in and explore why how to be different is the key AI design question.

Like it or not, AI is going to be at the heart of how we make things. I’ve personally been in hand to hand combat with this conclusion for a while. At Accenture Life Trends (was Fjord Trends previously) we spotted the significance of GenAI pretty early in our 2023 report, published in 2022. We knew it was big. That was clear from the moment Midjourney, Dall E and Stable Diffusion emerged in the spring and summer of that year and changed visual creation for ever. Then we got lucky with our publishing schedule, launching soon after ChatGPT and able to make timely comment on it. As we said at the time:

“As we went to press with this report, ChatGPT emerged, suggesting a big leap forward in AI’s ability to create accurate and useful text, which may become a major challenger to search engines.”

We also predicted issues around people’s fears of being made redundant, and what a world with limitless content would look like. We didn’t foresee therabots.

We’ve all been swept up in the drama since then. There is a lot about AI I am deeply concerned about – notably the way privately held companies have taken all the world’s content for free, diverted energy, water and investment from elsewhere for a technology that doesn’t always work, and the long term effect on society if we surrender many jobs and divert our attention even more to digital conversations, and away from each other.

In my last piece, which looked at how we designed the last 30 digital years, I said

‘You may be thinking, yep but I am not a designer. Truth be told, despite what my career signals to date, neither am I - strictly defined. So I am consciously using ‘design’ to mean a very broad scope here. Anyone who plays a role in building and delivering products, services and experiences over digital channels, plays a ‘design’ role – even if they do not wield a fistful of Crayola or use Figma.’

The difference now is we can all do design – or try to anyway. As ex-colleague and friend Andy Polaine used to say (somewhat caustically) ‘just because you can dance, doesn’t make you a dancer’. Nonetheless the new tools permit everyone to have a go. Some will use them well, some badly. So how we do we think about ‘design’ if we want to do it well? Does it matter? Is there a role for people who have ‘design’ in their title?

I’m going to show why the answers to these questions really do matter to everyone, especially those who create or reinvent products and services in the era of AI. There are three parts:

How AI changes design (it’s about driving intention)

The need to design the output of AI (it’s about the inherent need for differentiation)

Putting humans at the centre (it’s going to be about authenticity)

Part 1: AI Changes the Game of Design

If you want to understand what is happening to design, listen to what designers are saying.

Nic Roope, ex Antirom and former colleague, pointed out to me something in plain sight: AI has consumed the entire quantity of all human design so far.

This on its own facilitates the notion that everyone can be a designer, because they can draw on the sum total visual, service, interaction, experience design and art as seen through the lens of a diffusion or large language model. Before you object violently to this statement, I don’t really think it’s as simple as that. Some critical things are missing, and we will come on to what. However, if the AI labs have not yet got all of design to date under their belt, they soon will. And that is a core issue to deal with.

Sidepoint: a lot of web and app design – which mediates how most people experience digital products – reached maturity in the late 2010s. What I mean by that is that we knew by then, after a 20 year process of trial, success and failure, what a ‘good’ responsive website looked like, or where to signal ‘other things’ in an app (think top left hamburger icon). AI has ingested a lot of know how that is provenly replicable. Hold that thought for what comes next.

Just as importantly, AI changes the tools and practice of design. Tom Webb, one of the most thoughtful young designers I worked with at Fjord, is very clear – ‘the process we defined and knew is gone. Now we can imagine, create and iterate on the go – then play with it on the device’. There are a multiplicity of tools to help with this, for example: Canva, Figma, Adobe Firefly, let alone directly in the leading LLMs. Indeed Canva now advertise their brand in public spaces: recently outdoors at Waterloo Station, London. According to Little Black Book ‘It’s a bold, tongue-in-cheek celebration of how Canva empowers anyone, at any skill level, to design with ease, creativity, and impact.’

Using a combination of tools Tom ‘can create a full stack product’. But he warns you still need to understand what is happening underneath – a significant caveat. The result is that time to output has declined drastically. In a single day you can create concepts, define user journeys, bring these to life and A/B test with ‘synthetic’ audiences. Not only might this have taken weeks just three years ago, it can now be done by one person, not a team.

In fact the sequencing of when design is done may also have changed. Luke Wroblewski argues that as developers are moving at 10x their previous pace (I’ve heard this number from others too) they sprint ahead of designers who now ‘fix’ the UX, as opposed to the classic model, developed over the last 30 years, where designers define UX first and developers try to implement. Another, maybe bigger, impact might be removing layers of unnecessary process in large organisations as decision making could go from committee to individual. Back to this in a moment.

Years ago when I ran a mobile dating start-up, I saw for myself the quality improvement when a developer and a designer worked physically alongside one another on product rather than sequentially. Wroblewski sees this happening now, and in some cases:

‘an increasing number of designers are picking up AI coding tools themselves to prototype and even ship features. If developers can move this fast with AI, why can’t designers? This lets them stay closer to the actual product rather than working in abstract mockups.’

This is the direction people like Tom Webb have been moving in for a few years now, where designers also do some coding. Yet again design lines are getting blurred, as we saw in my last essay on digital design across the last 30 years.

What’s the end game here? Two trends to consider.

Let’s put ‘design’ aside for a second. What does all this mean for anyone who is making things? For entrepreneurs, products, service owners, brands?

To answer this, we need to look at two seemingly contradictory long term trends…

To learn about those two trends, why humans must be at the centre of design in age of AI, and much more, head over to Full Moon and subscribe:

Remember, subscribers to Full Moon get a monthly deep dive essay, as well as a monthly podcast, regular live Q&As with me and Mark, and the weekly Ideas newsletter. They can also choose one person aged 28 or under to receive one year’s complimentary membership.

Thanks for reading, and see you over at Full Moon!