Welcome to this essay from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on technology and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 20,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

🙌 This is instalment two of The Worlds to Come, an essay from NWSH. Go here to read the first instalment, or here to listen to it in podcast form. 🙌

It’s been a while

Earlier this year I published the first instalment of an essay, The Worlds to Come.

I promised the second instalment would follow quickly. That was months ago. So this email starts with a simple message: sorry for the delay. And to all those who wrote to ask, ‘where is part two of that essay?’, thanks for keeping the faith.

What happened? In short, life happened. This newsletter was born in the depths of the pandemic; I had time on my hands. But in the first quarter of this year other commitments — including my speaking schedule — accelerated back to full speed; it caught me off guard. I’m sure many of you can relate.

Still, in the grand scheme this is a small bump in the road. Writing to you every week is a huge privilege, and I love the community we’re building together and this journey we’re on to make sense of our shared future. This newsletter remains at the heart of my plans.

I’m going to send a note soon on what to expect from NWSH in the coming months, including a plan for longform essays and the return of the shorter notes that I used to send on Sundays — I really miss writing them.

But for now, here is the second instalment of The Worlds to Come.

This essay

This is an essay about systems of representation, virtual realities, and the way we understand our place in the world.

As a reminder, it’s not the typical NWSH fare. This essay is longer and more involved, but I hope also deeper, than the weekly updates. It’s an attempt to think with philosophy about virtual worlds and their implications for our orientation to this world.

Still keen to read? To refresh your memory, here is the table of contents for the whole essay:

Introduction: On the Threshold

1. What We Have Forgotten. Humans, language, and being-in-the-world.

2. Cast Adrift. A brief history of the Gods we made, how we banished them, and where that left us.

3. Crossing Over. Virtual worlds and the leap back to enchantment.

4. Conclusion: Where Next?

The instalment you’re reading will complete Part 1, leaving Parts 2, 3, and 4 still to come. Yes, this piece of work is better described as a short book than an essay. When it’s finished I’ll put the instalments together and publish the complete text as an ebook.

Given the time elapsed since I published the first instalment, let’s start with a brief recap.

Instalment One: a recap

If want to read first instalment in its entirety, you can find it here in text form and here in podcast form.

But a short recap of that instalment follows:

Introduction:

At the heart of this essay is a single idea: that our coming journey into virtual worlds can cause a transformation in our relationship with this world; one that can allow us to overcome nihilism, and again understand our lives as meaningful.

On first hearing, this claim seems impossibly far-fetched. I don’t believe that we’re set to disappear into the metaverse and live happily ever after. Instead, my interest lies in what virtual worlds can show us about this world and our relationship to it.

Specifically, I want to examine a set of more-or-less obscure relationships between virtual worlds, systems of representation, and meaning. My contention is that when these relationships are unpacked, virtual realities are shown to be the fullest realisation, or telos, of a certain orientation to the world: one that is mistaken, but that predominates among people who live inside modernity. And that because of this, our entry into virtual worlds can help us overcome that orientation and discover one that is more authentic.

Part 1: What We Have Forgotten

We humans are language animals. Aristotle calls us zōon logon echon: the animal that seeks meaning, the animal that speaks.

That idea is associated with another. That is, that we humans are subjective agents looking out to an external world, or a world-out-there. This idea, which we’ll call the subject/object framework, is embedded so deep in the heart of western metaphysics that it’s sometimes hard for us to see it. It underpins the modern scientific worldview, which sees us as conscious beings looking out to an external world made of atoms and energy.

In the early 20th-century, the German philosopher Martin Heidegger attacked the foundations of western metaphysics by exploding the subject/object framework. It’s not true, said Heidegger, that at heart we are subjects looking out to an independent world-out-there. Instead, the underlying truth about our existence is our inescapable unity with the world, which Heidegger called being-in-the-world, or Dasein.

Heidegger’s collapse of the subject/object framework proved one of the most influential — and controversial — ideas in all philosophy. It sought to overturn traditional western metaphysics, depicting that discipline as one long mistake: a series of conundrums and their attempted solutions based on the false idea that what is primary about our being in the world is subject/object.

Today, philosophers continue to build on the foundations Heidegger laid. There is even a small and growing literature that seeks to examine VR through the lens of Heidegger’s thinking. It’s that avenue of thinking that I want to head down in what follows.

We need to go on that journey step-by-step. And the next step is to ask: if Dasein is the primordial state of affairs for we humans, then how did we end up convinced that we are subjects looking out to an objective world-out-there? The answer I’ll give is language. Language itself is the radical disruption that severs us from Dasein. This has radical consequences for our understanding of virtual worlds. Because when language estranges us from Dasein, it starts us out on a journey that finds its fullest realisation in VR.

1. What We Have Forgotten (cont…)

(iii)

When we come to understand ourselves as subjects looking out to an objective world, the unity of self and world — of Dasein — is broken. We become a disengaged ‘knower’, who must try somehow to hook up to and have knowledge of the ‘world out there’.

This is an estrangement from the underlying truth (as Heidegger would have us understand it) of self-world unity. How does this estrangement come about?

Heidegger’s answers were complex. Essentially, he believed that we become estranged from the truth of Dasein when something causes us to step back from our engaged agency and try to analyse it. That can happen when our engaged agency is interrupted by some error or fault — when, to return to our earlier example, the hammer that we are using breaks and our hammering comes to a sudden end.

What lies submerged in Heidegger’s analysis, though, is a deeper and more radical answer. It is that language itself is at the root of the processes that sever us from Dasein.

This, I should admit, is a controversial reading — some might argue a misreading — of Heidegger. It does have roots in his thinking: he writes a lot about how the misuse of language is one of the processes that estranges us from Dasein and establishes the subject/object framework. But he also says that ‘language is the house of Being’, which has widely been interpreted as meaning that language and Dasein are bound together. Overall, Heidegger’s beliefs on the relationship between language and estrangement from Dasein remain somewhat opaque, and are the subject of ongoing debate.

So why do I contend that language is the driver of our estrangement? First, we need to remember what this estrangement consists of. Dasein, or our being-in-the-world, constitutes a fundamental unity between self and world: a me-world. In that state of affairs we don’t hold the world apart from ourselves and examine it at a distance. Rather, we are one with it in a process of engaged agency. We know a hammer not as an independent and objectively-existing object, but as part of a network of meanings that taken together form our understanding of and grappling with the overall scene.

But the stance we take towards the world when we become language-bearers is, it seems to me, antagonistic to all that. The very fact of having the word hammer necessitates, already, a framework in which there is me and the hammer — it necessitates a break from the me-world, and the establishment of a subject/object framework that underpins our conception of the world-out-there.

I contend that it is the event of language that is the break point. That is, language is what severs us from the primordial oneness that is the me-world, and establishes the subject/object framework that creates, for us, an externalised world-out-there (which we typically call, simply, the world).

What can we find in Heidegger to support this idea? Heidegger’s thinking on the way we know a hammer, or anything else, involves a tripartite model of ‘primary understanding’ that he calls fore-structure, fore-having, and fore-conception. He seems to believe that aspects of this understanding are pre-linguistic; that is, they do not depend on language. There are times when he gestures towards the idea that it is the event of language that breaks us out of primary understanding and into the subject/object model. But at other times he steps back from this. The moment of severance remains obscure.

What is more clear, though, is that Heidegger agrees that once the subject/object framework is established — whatever the cause — then language tends to further the estrangement from Dasein that this framework constitutes. Language causes us to crystallise our sense of objects as independent entities, uprooted from the network of relationships that renders them meaningful within Dasein. Language is the process that allows us isolate objects as objects, and hold them in our attention. It fuels our ability to exit engaged agency and instead undertake various forms of high-level theorising in which we become disinterested ‘knowers’ looking out to a world of independently existing entities. Heidegger refers to the ways in which language estranges us from the truth of Dasein when he talks about ‘idle talk’: language that immerses us in a theoretical, or inauthentic, versions of our being.

If we come to believe that language enacts our estrangement from Dasein, then we can see it as performing a strange and paradoxical double function. Language at once constitutes the human mode of being, and yet estranges us from that being in its most fundamental form. And because language is the very medium in which our thinking on this matter takes place, the ways in which language performs this double function must remain mostly opaque to us. As language-bearers trying to understand the impact of language on our mode of being, we are like fish trying to understand how it feels to be wet.

We might, then, come to believe that language is best understood in the same way that physicists understand a singularity. That is, as an object at which the laws that govern our understanding of the world break down. It’s my contention that this is just how we must understand language. As the singularity at the heart of our being.

The idea that language estranges us from some deeper, primordial connection with the world is far from new. The 20th-century philosopher Ernst Cassirer, who spent a lifetime analysing symbolic representation and systems of meaning, believed that our experience of the world comes via symbolic systems that interpose themselves between us and reality:

‘No longer can man confront reality immediately; he cannot see it, as it were, face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves, man is in a sense constantly conversing with himself.’

Nietzsche said ‘words brutalise’. The primitivist philosopher John Zerzan argues that ‘language may be properly considered the fundamental ideology, perhaps as deep a separation from the natural world as self-existent time.’

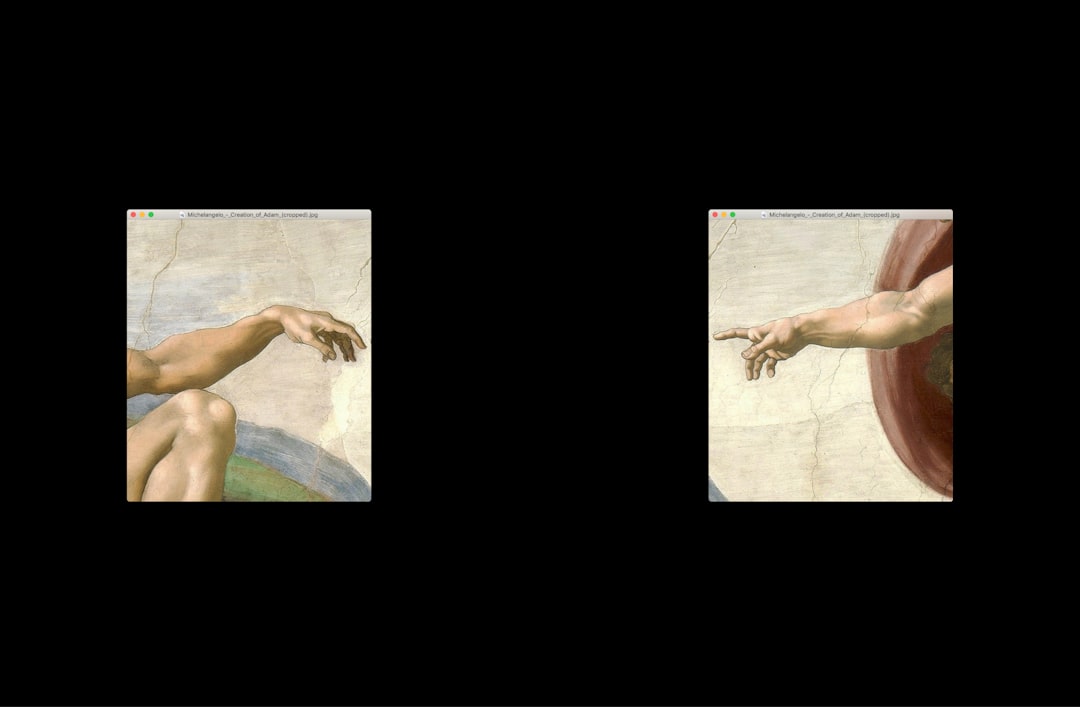

Meanwhile, latent in some of the oldest stories in our culture is the idea of language as a deep form of estrangement.

When God banished Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, he also banished them from the original, Adamic language. To leave the Garden was to forget the language of God; the ur-language that gives everything its proper name. Instead, we are cursed to use false languages of our own making — to use artificial words that do not truly refer to the world.

At the heart of European culture’s ultimate origin story, then, is a message about our estrangement from the world, and the role that language plays in that estrangement.

The Edenic harmony we’ve forgotten, and the right language associated with it — is it best understood as Dasein?

(iv)

We have travelled a long way from our central concern: virtual realities. But the terrain we’ve covered has deep implications for the emergence of virtual worlds and their impact on our relationship with this world.

How are these apparently separate topics — language as estrangement, and VR — intertwined?

When we say that language estranges us from the primordial oneness that is the me-world, what we’re saying is that a system of symbolic representation is responsible for this estrangement. VR is a system of representation, too. So if we believe that language estranges us from Dasein, then it seems reasonable to believe that virtual worlds will also have consequences for our relationship with Dasein.

It’s my contention that virtual worlds can, just as language did, shift our relationship to the me-world.

What comes next, then, is to investigate the nature of this shift. And if we’re going to do that, we need to dive deeper into the estranging properties of language. To fast-forward somewhat, the conclusion we’ll be pursuing via that investigation is that when we understand the processes via which language estranges us from Dasein, we come to see virtual worlds as the end point, or telos, of those processes. This has profound implications for the way VR can reorient our relationship with world around us.

As we’ve already seen, the idea that language is in some sense estranging is old. But what are the mechanics that underpin this estrangement? How is it exactly that language operates to estrange us from the me-world? Far less has been written on this subject, but I want to attempt an account. Specifically, I want to argue that this estrangement comes via a hidden double inversion enacted by language.

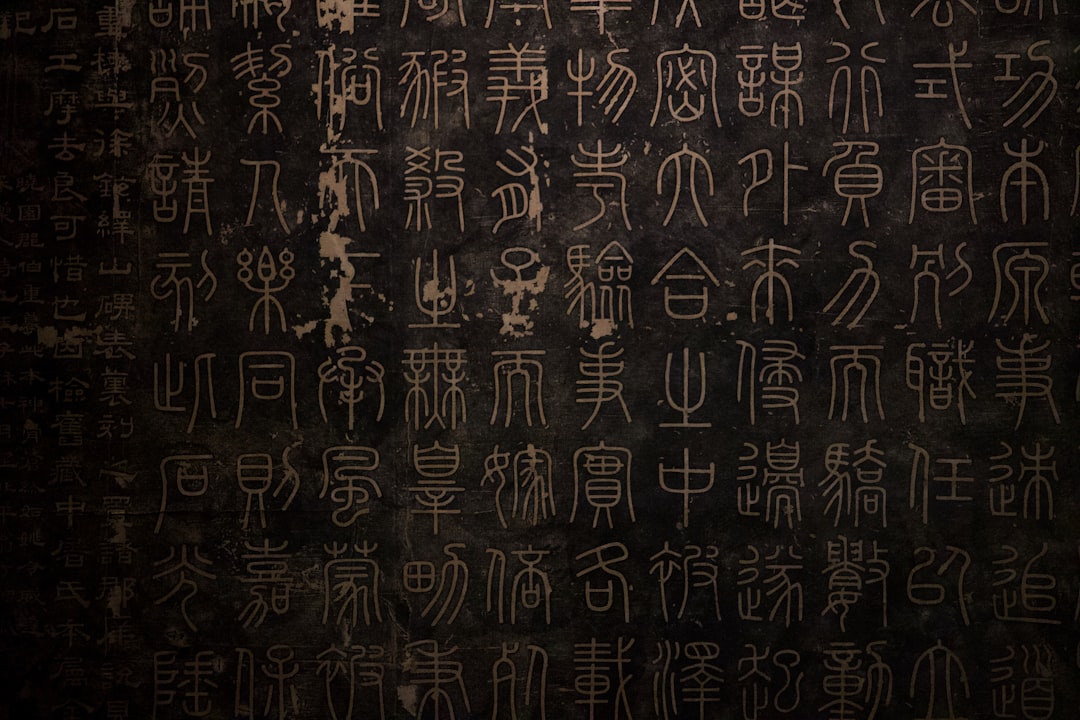

So what is the nature of this double-inversion? To start, let’s address a simple question with a complex answer. What is a word?

A word is a sign that points to something else. That something else may be an object, ‘table’, or an idea, ‘the number four’, or a sentiment, ‘thanks’.

The word-sign is made of two halves. There is the sound (in the case of a spoken word) or markings (in the case of a written word) that is the token that we pass between one another when we use the word. Then there is the concept that this token signifies.

In the late 19th-century the seminal linguist Ferdinand du Saussure articulated a formal model that captures all this. Saussure called the word’s symbolic form – the spoken word or written markings – the signifier. And the concept to which it referred the signified. The actually-existing thing to which to the word refers is the referent.

The classic Saussurean diagram of a sign, then, looks like this:

Here is a specific example dealing with the French work arbor, which means tree:

Saussure wanted to articulate the necessary structure of language as a symbolic form. Specifically, his model highlights the way that any language relies on a set of concepts, and on an agreed relationship between each concept and a specific speech sound or marking. For a word to function, all of that is needed.

Crucial to Saussure’s view of language, too, was the view that it does not merely describe our view of the world; rather, it constructs that view. Early language users did not attach speech sounds to mental concepts that already existed for them; instead, the emergence of language was a key part of the process that brought those mental concepts into being. As Saussure has it:

‘...if words had the job of representing concepts fixed in advance, one would be able to find exact equivalents for them as between one language and another. But this is not the case.’

The coming into being of language, then, means the coming into being of a set of concepts that mediate our experience of a world-out-there. Insofar as we experience ourselves as moving through a world of tables and chairs, badgers and rocketships, and all the rest, those concepts make that experience possible.

Here, then, are the briefest outlines of Saussure’s model of language; a model that exerted vast influence on so much linguistics and philosophy that came afterwards, and that still predominates today. Words are made of a signifier and a signified. Language does not merely describe a set of ordered concepts that exist pre-linguistically; rather, the event of language brings those concepts into being. In this way language does not simply describe our experience of the world-out-there; in some deep sense it brings that experience into being.

So while the me-world was a realm of direct experience, our experience of the world-out-there is mediated by concepts. And here’s the important point for our purposes: already present in that mediation are the seeds of a strange inversion.

Consider the way we typically think about the relationship between language and the world-out-there. We generally believe that the world-out-there itself is the ground on which our representations are built; that there are objects (the real) and then our representations.

But look closely at the mechanics of language as outlined by Saussure, and the nature of the inversion I’m talking about becomes clear. In order to function as part of a language system, our mental representations must become in some sense, for us, foundational; the ground against which we compare our experience of the world. Instead of telling ourselves that our representation of a table is merely like the tables we see in the real world, we look at a table in the real world and say it is merely like our representation. Our representations become prior, in some sense more real to us, than the world-out-there. This doesn’t happen become of some error or decay in the way we use language; this inversion is a property of language itself. Language depends upon a set of concepts that must become, for us, foundational: a secure ground against which we judge the world-out-there as we encounter it.

Perhaps this accounts for something of the strange, hallucinatory aspect of human experience. For we language-bearers, the world-out-there is at once an objective reality but also a kind of shadowland: a realm of signs that point back to the more foundational reality of our mental concepts.

A dimly-grasped awareness of this inversion — of the real as a domain of signs and signs as a domain of the real — runs through the history of western thought. The most famous example is one of the earliest: as we saw in the first instalment of this essay, Plato’s theory of the Ideal Forms tells us that real horses are mere shadow entities that point towards their Ideal Form counterpart in the realm of ultimate reality, which is the realm of the Forms.

Plato believed in the literal existence of the realm of Ideal Forms. We cannot join him in that belief. But doesn’t the continued power, for us, of the theory of Forms lies in its oblique articulation of the strange inversion that language enacts? An inversion that sees the world-out-there turned into a shadowrealm, which points back to the more-real domain of our mental representations.

Isn’t that the strange truth that Plato’s theory continues to whisper to us, from a distance of 2,500 years?

(v)

The phenomenon that sees our mental concepts become in some sense more real to us than the world-out-there is one part of the estranging nature of language. It is the first part of the double-inversion I want to describe.

But once the world-out-there is established, a second and related estrangement takes place. This is the second inversion. The mechanism at work here is made possible by language, but relies directly on another form of representation: iconic representation. As we’ll see, via the second inversion that iconic representation enacts we project our estrangement from the world back into the world, so that the boundaries between our representations and the real become blurred.

How does this happen?

Language is a symbolic form. That is, a form of representation in which one thing is held to stand for another. Iconic representation, on the other hand, is the use of direct pictorial representation of what is being represented; it is the form of representation in which an image of a thing is used to represent that thing.

To understand the estranging power of iconic representation, we must first understand the relationship between iconic and symbolic systems of representation. This relationship is not ordered as we tend to think.

Intuitively, we tend to feel that iconic representation comes before symbolic representation. Specifically, that iconic representation must have emerged sooner in our evolutionary history, because it is a simpler and more fundamental type of representation that would have been available to primitive humans who were yet to achieve the sophistication needed to develop symbolic forms.

In fact, both a theoretical examination of the nature of iconic and symbolic forms and a look at the actually-existing evidence leads to the opposite conclusion. Symbolic representation comes first, and provides the foundations on which iconic representation is built.

I am once again on contested ground with this claim. Mainstream semiotics has reached no definitive conclusion on whether humans first adopted iconic or symbolic representation.

This 2007 paper looks at the adoption of iconic representation by pre-school deaf children, and finds that those children do not start using iconic representation before they start using symbolic. Instead, use of iconic representation seems to kick in around the age of three, and the ability to recognise an iconic sign as such is heavily influenced by the ability to label — that is to have a word for — the referent of the sign. Other studies, say the authors, also point to the idea that use of iconic representation is tied to, and in some way dependent on, use of language.

It’s also to be noted that the earliest pre-historic cave paintings known to us are not iconic representations. Instead, they depict abstract patterns. Some scholars have even argued that the patterns are intended to stand for something; that is, that they are early forms of symbolic representation. It’s only thousands of years later, it seems, that humans started to create iconic representations of themselves and the creatures they saw around them.

This evidence is limited. But it supports the idea that iconic representation depends on language. This idea also flows from Saussure’s conviction that language is not simply a tool that allows us to describe the world-out-there as we have already found it, but instead is a lens that actively constitutes our view of that world. It’s not, then, that we have a pre-existing set of mental concepts and then language arises to attach a word to each concept. It’s that part of the arising of language is the very bringing into being, for us, of those concepts and their ordering function. Language in this view is not merely descriptive, but also constitutive.

A way to state all this is plainer language is to ask: do bisons exist for us before we are able to say the word bison?

For those who believe that language is constitutive, the answer is no. The ability to see a bison as a bison, and then to draw a picture of a bison on a cave wall, is dependent on the ordering function that language brings to our unmediated experience. Dependent, that is, on the development of a set of shared mental concepts that allow us to distinguish a bison from a not-bison. And the development of those shared concepts and the symbol-tokens that we associate with them literally is the development of language.

So, language sets the stage, as it were, for iconic representation. And this is important for our purposes, because iconic representation fuels the second part of the double-inversion we’re investigating.

This second inversion sees us take our mental concepts — the concepts that underpin language — and project them into the world-out-there in the form of iconic representations. In so doing, we create an environment populated by reproduction, by copies, and then copies of copies. Over time, and via new technologies — the printing press, photograph, video — those reproductions become ever-more sophisticated. Eventually, we find ourselves immersed in a world of reproductions that ever-more closely resemble the world-out-there. Soon enough, we arrive into a state that is highly recognisable to all of us who inhabit modernity (or, some might want to say, post-modernity): a tech-fuelled hall of mirrors in which the boundaries that separate image and reality seem to fade away. We have come to live, at that point, inside what the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard called hyperreality; a universe of signs that point only to one another.

To recap: first language severs us from the primordial oneness that is the me-world, and establishes a world-out-there that becomes, paradoxically, a realm of signs that point back to our mental concepts. Next, we project our mental concepts back into the world-out-there in the form of representations. Soon enough, the boundaries between the world-out-there and our representations of it start to fade away. A journey that began with language has led us to immersion in a hyperreal world of representation-reality.

It’s striking how this journey and its destination accords with Heidegger’s own descriptions of what it means to be estranged from Dasein.

When we establish the subject-object framework, said Heidegger, we externalise the world and then establish a relationship of objectification and control over it. As we can in the first instalment of this essay, objects that were once ready-at-hand — unified with us in a process of engaged agency — become merely present-at-hand: externalised and seen through a framework of ‘me’ and ‘world’

The relationship of objectification and control that results, Heidegger believed, underlies the west’s defining project. That is, a project in science and technology that sees the world as a resource over which we must achieve mastery.

Notice how this relationship of objectification and control is enacted, too, by the double inversion I’ve described and the hyper-real image-world that it leads us to. In 2022, we reproduce reality over and again with obsessive fervour, demanding reproductions that ever more closely approach our experience of the world-out-there: pictures, photographs, cinema, high-definition video. We demand access to all every part of the real at all times. From the comfort of our beds we summon a sunset, the ocean, the Sydney Harbour bridge, a fruit bat.

Today, we moderns move inside a world of representations — from TV, to Twitter, to TikTok — beyond the imagining of the earliest humans. Probably, it is beyond anything that Heidegger imagined, too.

What’s more, our gateway into that matrix is a granite-black slab no bigger than our palm. We have put the entire world in one hand, and now we can’t stop looking. Heidegger’s strange vocabulary for the subject-object framework — his talk of presence-at-hand — has achieved a new and eerie reality.

(vi)

It has been my aim in this section to identify, and anatomise, the severance from Dasein that language enacts.

Starting with the basics of language — signifier, signified, and referent — we’ve arrived into the hyper-real hall of mirrors that we moderns inhabit in 2022.

To live in this hall of mirrors is to be surrounded by phantoms. Copies of copies that are, for us, at once the real and unreal.

The copies in which we are immersed are iconic, or direct, representations. But because we are symbolic animals, it’s possible to discern in our relationship to them a submerged symbolic effect. The representations that surround us become, for us, symbols of our estrangement from the world. It seems to me that this accounts for something of the schizophrenic relationship we have with these representations. We crave them; they bring us pleasure, comfort, beauty, and endless distraction. At the same time, they leave us with an oblique feeling of emptiness.

In the next section, I want to look at that feeling and what underlies it. Specifically, I want to dive into the deep relationship between systems of representation and nihilism: the fear that no meaningful relationship exists between ourselves and the world that we find ourselves in.