Post-Human Economics

An essay from The Exponentialist

Welcome to this special update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 30,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

It’s been too quiet around here recently.

Which is, of course, my doing. I’ve been working on a couple of big projects across the summer; time has been, to say the least, at a premium. The real point is: both projects have major implications for the future of this newsletter. I can’t wait to share more on all that in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, though, I’ve still been writing a whole lot. As most of you know, along with Raoul Pal I run The Exponentialist, a community focused on emerging technologies and their economic, social, and human implications.

In this special update, then, I’d like to share a recent essay from The Exponentialist. One that allows you a glimpse of the kind of work I do there. And that articulates an set of idea that are at the heart of my current thinking when it comes to our journey into the decades ahead.

The essay introduces a theme I’ve been developing for a while now. It is about post-human economics and a great coming civilisational quest to create more intelligence per unit energy.

This is an attempt, really, to envision a world in which abundant AI and robots have replaced human as labour inputs into the economy, and have created conditions of radical knowledge and material abundance. When this happens, everything we know about the economy as it exists today starts to break down. I want to try to make sense of that. And of what comes next.

In this essay I make a few mentions of last month’s essay. That piece argued that in a post-human economy, GDP is no longer a coherent measure of economic flourishing. But all that is recapped in this essay; everything you need to understand this piece is contained within it.

These kinds of essays go out to Exponentialists every month, along with a tech-focused investment portfolio, monthly community chats with me and Raoul, and regular guest interviews. You can go here to learn more about The Exponentialist.

But that’s enough preamble. Let’s get into it.

Post-Human Economics

What am I talking about when I use the phrase post-human economics?

The idea is tied to another, one that sits at the heart of my thinking on the Exponential Age. That idea is the coming economic singularity. It’s really this idea that I’m trying to extend — trying to fathom — when I talk about all this.

So the next question becomes: what do we mean by the economic singularity? In physics, a singularity is a point in spacetime where all the usual rules of physical reality break down.

The economic singularity thesis says that now, and via the convergence of a set of transformational technologies, we’re moving towards a transition that will see all the old rules and norms of the economy break down. Via that transformation, the categories and very language we’ve always used to describe the economy will fall into incoherence.

Increasingly, this idea is the focus of my thinking. My research is converging around a set of related questions. What is the path to this singularity? What does the transition phase look like? Is it possible to peak beyond the event horizon and understand the nature of post-singularity economic conditions?

Developing the idea of a post-human economics, then, is really about forging a new way to model all this. It’s a new language via which to approach the Economic Singularity.

In last month’s essay, I played with this idea. The transition into the singularity, I said, can be understood as a transition from an economy built on human inputs and conditions of scarcity — that means material, cognitive, and labour scarcity — to an economy built on automated inputs and conditions of radical abundance. And under those conditions, GDP no longer makes sense as a measure of economic flourishing.

In this essay, I attempt to push that idea to its logical conclusion. I do that by asking: if GDP is not a valid measure of economic flourishing inside a post-human economy, then what is? What should we measure?

My answer? Eventually, the most coherent measure of flourishing will be around how efficiently our civilization converts energy into intelligence. That is, it will be intelligence output per unit energy. In the post-human economy, everything lies downstream of better and more abundant intelligence. And under those conditions, the economy becomes an endless, relentless quest to maximise that metric.

When we understand the path to that world — a world in which intelligence output per unit energy is the best measure of flourishing — something amazing happens. We’re empowered not only to understand the transition from a human to a post-human economy, but to glimpse beyond the event horizon of the singularity, to the outlines of the post-human economy itself.

Just as it sounds, I’m attempting with all this to push my thinking to the very edges; to model the shape of the radically new world that is coming.

Figuring all this out means trying to piece together a seven-dimensional puzzle that none of us understands. I’m thinking aloud, step-by-step, and trying to make sense of it all. So treat all this as just one further step in a long journey, which is always subject to revision. The work of making sense of what’s happening now — of the emerging Exponential Age — is only just beginning.

So, let’s start.

*

The Handoff

Before we get into the argument on intelligence output per unit energy, we need to revisit a prior question. What are the practical forces at work pushing us towards a posthuman economy?

Remember, we currently inhabit a human-centred economy. That means one built around human needs. One built on human inputs. And one enacted around conditions of scarcity; material scarcity, scarcity of human labour, and cognitive scarcity, too.

Those conditions are now being overturned. But how? I went deep into this in my last essay. And really, everything I’ve written about the Exponential Age can be deployed as an answer to that question. The answer, in a word, is technology. Technology is overturning those conditions.

But at the heart of the story are robots, especially humanoid robots. And AI, especially AGI, or superintelligence. They are the central path to a post-human economy.

When it comes to humanoids, advancement has been rapid over the last couple of years. Look at what’s happened in just the last few weeks.

The US humanoid startup Figure released HELIX, an AI that blends a sophisticated LLM and reasoning model with advanced machine vision. The result is a robot that can understand natural language, reason about its physical environment, and then take appropriate action. This means it can perform everyday, unstructured tasks via ordinary spoken instructions.

As Figure showed in their demonstration video, tell their 02 robot to ‘tidy the kitchen’ and it will now understand that celery goes in the fridge and canned fruit goes in the cupboard, even if it has never seen these objects before. And it can act on that understanding.

Other big players have just released similar models, too. DeepMind’s Gemini Robots and Nvidia’s GR00T N1 both allow humanoids to understand, reason, and act.

Right now, most of the humanoids on trial inside workplaces, such as Amazon fulfilment centres and BMW factories, are performing the same structured task over and over again. But HELIX and these other models are a key step towards humanoids that are able to work independently in everyday environments, taking a loose set of instructions such as ‘keep this place tidy’ or ‘sort these packages’ and acting on them in a coherent way. There’s still work to be done, but we’re getting closer to a ChatGPT moment for humanoids.

Meanwhile, as I wrote about at the start of the year, AGI feels ever-more imminent.

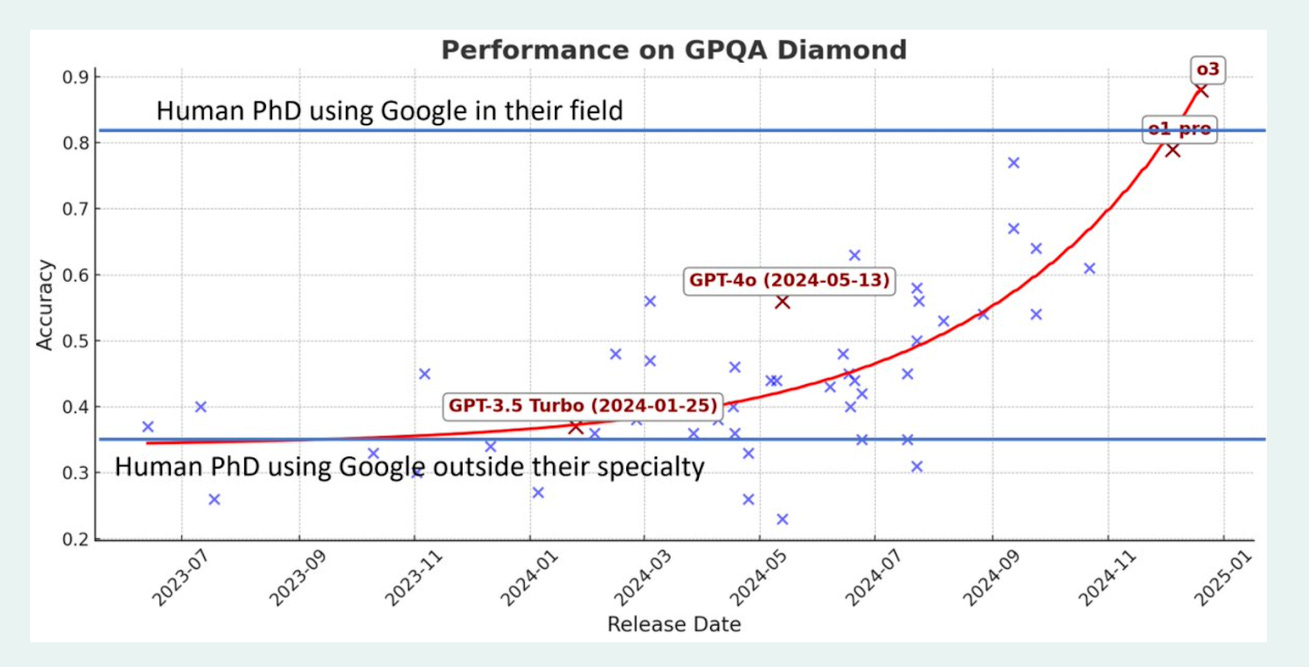

OpenAI’s o3 remains the frontier model for now. A reminder: look at its performance on the GPQA Diamond benchmark, a set of super-hard science and maths questions. It’s so good that it outperforms human PhDs who are answering questions in their specific scientific domain and who are allowed to use Google to help.

That’s why I call this The Last Chart. It’s the final chart we get to make as Earth’s apex intelligence. After this, we hand the baton to the machines:

Okay, there’s a little hyperbole at work in that statement. But not much.

Put this all together, and what is happening? The iconic technologist Kevin Kelly — co-founder of Wired magazine and a Silicon Valley legend — wrote a blog post recently that sums it all up so well.

That post was called The Handoff, and it taps into another core idea in Raoul’s work: demographics are destiny.

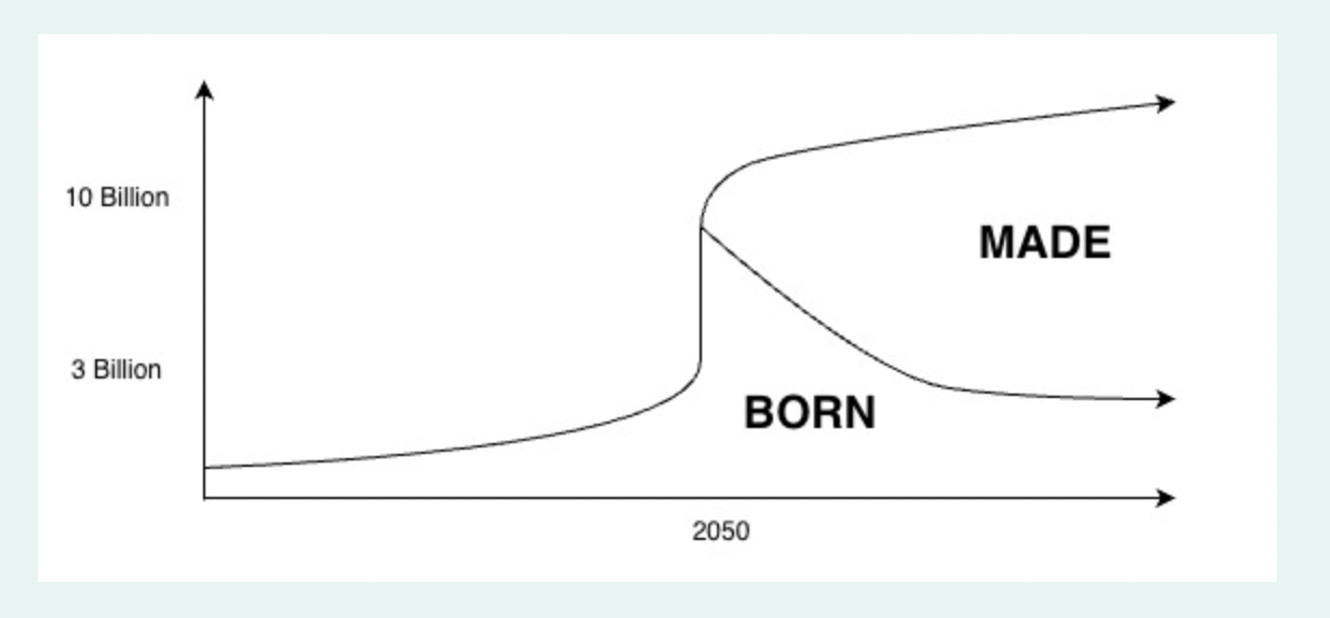

In the developed world, said Kelly, we’re about to hit a historic moment. The human population is about to peak and then start to decline — the first time that’s happened inside modernity. Meanwhile, billions of AI agents and tens of millions of humanoids are about to come online. They are the new worker population. When we think demographically, we can no longer think only about the entities that are born — the humans. We need to count the entities that are made, too — the AIs and robots.

What’s happening now, said Kelly, is a historic transition. It’s an economic handoff from we humans to the AI and robots we are creating.

If we accept this vision, the question becomes: what does this handoff do? What is the nature of this shift? The answers are far reaching: This shift will rewrite the underlying logic of the economy, transitioning it from an economy built on human inputs and conditions of scarcity, to one built on automated inputs and conditions of radical abundance. We move, in other words, towards a post-human economy.

I went deep on this process in last month’s essay.

First, AGI and agents will eliminate scarcity across many knowledge work domains. Across many services and knowledge-based industries — coding, law, marketing, consulting, finance and more — production of outputs will be substantially or completely automated. We’ll see the rise of instant, hyper-personalised, zero-cost production.

Eventually, this phenomenon will move beyond services and into physical products, too. Abundant energy will converge with humanoid robots and next-generation manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing to push the cost of much physical production down to something negligible.

In the next section, I want to zero in on this transition. What are its implications? And what is the nature of the new economic reality it is leading us towards?

Another question can act as a kind of proxy for these deeper, more complex ones. In the new world that is coming, what will we measure?

*

What Do We Measure?

We know what we measure now. Inside the human-centred economy we’ve built, GDP is the principal measure of flourishing.

But as we saw in the previous essay, as we transition towards a post-human economy, GDP starts to become incoherent as a measure of anything meaningful.

Automated outputs across much of the knowledge and services economy will push prices to zero. Eventually this will move to some physical products, too. So we’ll see huge economic welfare gains — lots of great new stuff! — that is not captured by GDP.

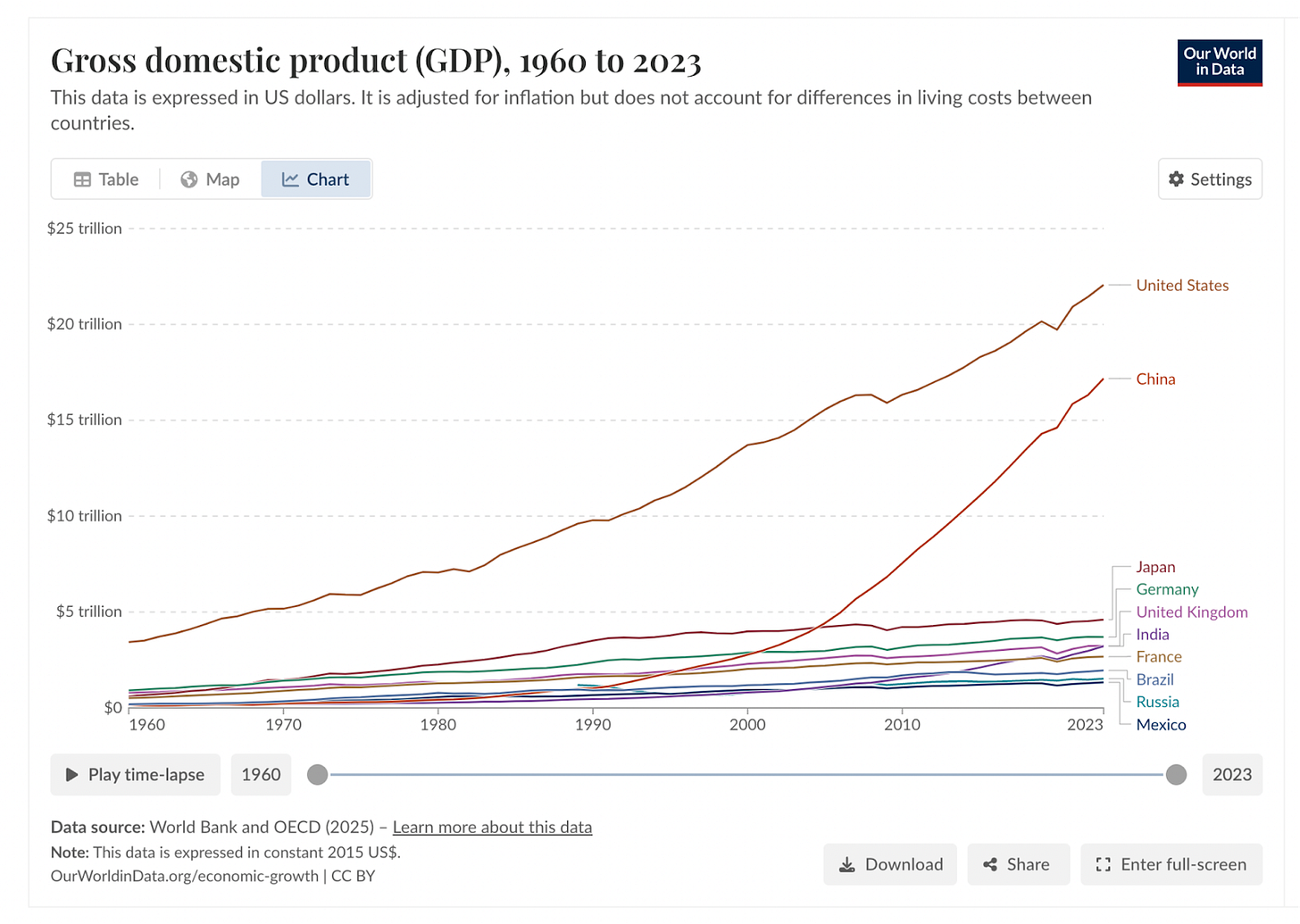

At the same time, we’ll see AIs transacting with AIs in lots of ways. This could produce skyrocketing GDP growth rates — 10%, 50%, 100% per year — via activity that is entirely divorced from any impact on we humans or our wellbeing.

Once we get there, what does GDP even mean? And if we don’t measure GDP, what do we measure? If we understand the answer to that question, I think we understand so much more.

Remember, GDP makes sense inside a human-centred economy in which the fundamental condition is scarcity. GDP is essentially the scorecard we use in answer to the question: to what extent are we overcoming scarcity? So if we can pin down the fundamental measure of success inside a post-human economy, I think we be able to glimpse the fundamental nature of that system.

The big idea I’m playing with at the moment? In the post-human economy that is coming, intelligence itself becomes the primary metric.

Just as the human-centred economy pursued GDP, so the post-human economy will pursue intelligence output, or what I call intelligence value.

That’s because in that world, everything is downstream of better and more abundant intelligence. Scientific and technological breakthroughs, more advanced and cheaper healthcare, finance, knowledge work, manufacturing, logistics, everything comes down to intelligence.

In this environment, the primary economic goal shifts towards the efficient conversion of resources into intelligence. The more we do that, the more we flourish.

The fundamental constraints when it comes to intelligence production are cost and energy. That means the cost of producing the intelligence stack: the chips, the data centre they will live in, the running costs, and so on. And then the energy to run that stack.

To be more specific, then, what gets measured is intelligence value per dollar per unit energy.

What I think we’re going to see in the decade ahead is a shift towards a civilisational system that has this imperative at its heart. In so many ways, this is the big transition that’s coming. It’s the transition that most characterises our march into the Exponential Age. We move from a system that measures GDP, to a system that measures intelligence per dollar per unit energy.

We’re getting closer, now, to understanding more about the true nature and shape of a post-human economy.

But to get closer still, we need to zoom in. How does the transition to a post-human economy play out in practice? What are the mechanics at work here?

Intelligence Markets

We know what happens when a resource becomes valuable. Markets emerge; those markets match buyers of the valuable resource with providers of it.

I think we’ll see the emergence of markets of this kind around intelligence output. Humans, and eventually AIs themselves, will bid for access to the future outputs of AI models. That will be about saying: I have a knowledge task that I need to get done. So I want X amount of intelligence output from this particular AI model. What do I need to pay? The market will determine that price.

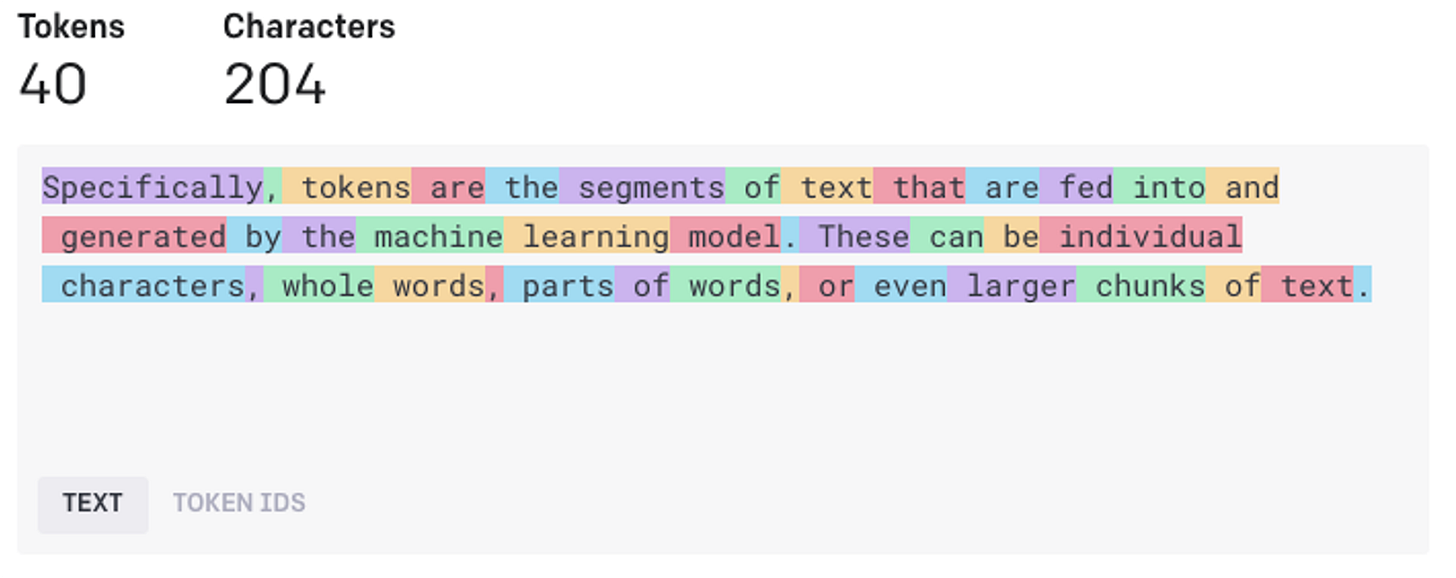

Remember, LLMs give their output as tokens. Put simply, one token is just a certain number of words outputted by an LLM.

So we’ll have humans and autonomous systems trading access to a certain number of future tokens provided by a certain AI model. I want access to 1,000 tokens from this open-source model. What do I need to pay?

We can see the emergence of these kinds of markets now in platforms such as SingularityNet, which styles itself ‘an open and decentralized network of AI services made accessible through the blockchain’.

On the platform, providers of AI output and other intelligence services can charge for that service using SingularityNet’s native AGIX cryptotoken.

Eventually, these kinds of markets will act as vast sorting machines for access to intelligence. Buyers of intelligence, or tokens, will seek the most intelligence value for their dollar. Meanwhile, providers will be incentivized to supply great value. That will mean building an intelligence stack — the chips, data centre, energy source — that gets the most tokens per dollar per unit energy from a particular AI model.

This is how markets will drive forward the efficient provision of intelligence.

The central thought here is that In a world in which everything is downstream of better and more abundant intelligence, the economy becomes a relentless, market-driven quest to improve intelligence output per dollar per unit energy.

These markets will also provide the information we need to measure this quest.

They’ll do that by becoming giant social consensus machines for ranking the intelligence value provided by AI models. Let me explain…

Part of the challenge associated with the idea that intelligence per dollar per unit energy becomes the principal measure of flourishing is that ‘intelligence’ is extremely hard to quantify. It’s abstract, intangible, and multi-faceted. Sure, we have IQ. But that’s really just a way of ranking humans against one another via their performance on a single test. It’s far from perfect, and once you get several standard deviations away from the (by definition) population average IQ of 100, it probably becomes somewhat meaningless.

Intelligence markets will provide another, far more thorough way of ranking the intelligence of different AI models. Essentially, the market will provide an answer on the intelligence value provided by any specific AI. If one token of output from model A costs $1 dollar, and one token from model B costs $10, then the market is telling us that model B is more intelligent — that one token from model B provides greater intelligence value.

This will be, then, a market-determined, social ranking of the intelligence of AI models. And when it comes to intelligence, a social determination is probably the best kind; after all, it’s how we’ve always done it with each other. An IQ test may say that someone is not very intelligent, but if your own interactions with a person — and the general crowd consensus — says otherwise, you’ll believe that over the test.

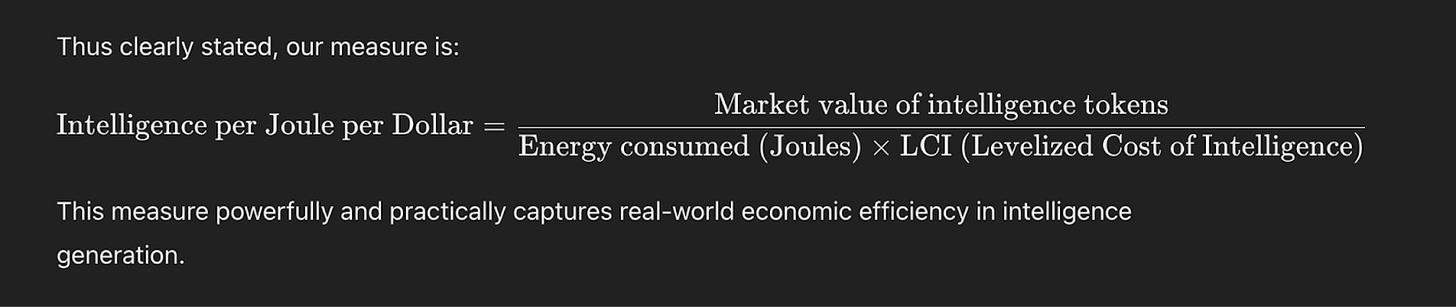

This market ranking of intelligence value will allow us to calculate the intelligence value per dollar per unit energy provided by a specific AI stack. The calculation will look like this:

As you can see, this calculation makes use of a concept borrowed from the energy industry: levelized cost. When used for solar panels, the levelized cost of energy calculates the cost of energy produced by the panels by factoring in the upfront capital costs of making the panels, the operational costs, and the expected lifetime energy output.

Similarly, for an AI intelligence stack, our levelized cost of intelligence should incorporate the upfront cost of building the stack — the cost of model development, the chips, the server infrastructure and so on — as well as the running costs including maintenance and energy.

These are the details, but the key point here is that this becomes the principal measure of economic flourishing. Intelligence per dollar per unit energy becomes the game.

There are two ways that can work in practice. We could take the best intelligence value per dollar per unit energy provided by any AI stack as our indicator of broader socio-economic flourishing.

But it may make more sense to take the average that is being achieved by the entire civilisation. The higher we push that average, the most intelligence value we are outputting per dollar per unit energy. And the better pretty much everything will be.

There’s a crucial point to be made here; one I’m sure many of you have already picked up on.

We are still in the realm, with all this, of transition to the post-human economy. We’re still talking about the cost in dollar terms of intelligence; this means we’re still operating under conditions of material scarcity. And we’re still imagining human actors operating inside these intelligence markets, bidding for the access to AI tokens alongside.

As we’ve already established, in a truly post-human economy conditions of material scarcity are replaced by those of radical abundance and negligible costs. And humans are cut out of the loop. So let’s push our vision further; what do intelligence markets look like when those conditions pertain?

*

The Final Metric

How does the transition to a fully post-human economy occur?

The answer is via the set of processes I’ve written about across these two essays, and many times before.

AGI, humanoids, and other next-generation manufacturing techniques will push the cost of designing and making new AI chips down to something negligible. AGI automates the design. Humanoids and other robots handle the manufacturing of chips, and construction and ongoing maintenance of data centres.

This, combined with abundant and zero marginal cost energy pushes the levelized cost of intelligence close to zero. Yes, we’re some way from all that right now. But it’s coming. And when it does, we are thrown on to an even more fundamental measure of economic flourishing.

The per dollar part of our measure is no longer relevant. We’re left with intelligence value per unit energy.

The shift from intelligence value per dollar per unit energy to simply intelligence value per unit energy signals a profound and historical transition moment. It represents the shift from traditional human-centered economics — an economy built around human inputs and scarcity — to a post-human economics driven by material abundance and intelligence.

Burn this metric onto your brain; my conviction is that it becomes of central importance in the decades ahead. Intelligence value per unit energy is the end game. It is the core metric in a post-human economy. And in some deep sense this metric is the purest measure of civilisational flourishing that there can be. How efficiently does this civilization turn energy into intelligence? Answer that, and you’ll know so much else that is important about that civilization; its science, technology, healthcare, manufacturing, and more.

Meanwhile, in a fully post-human economy there will be AIs trading intelligence tokens with other AIs. Humans are cut out of these markets, or (more likely) their participation in them becomes inconsequential.

Imagine an AI that wants to perform a particular knowledge task — one that it can’t complete on its own in the timeframe available. It will go to market and bid for the tokens it needs. The currency in use could be a stablecoin that represents units of energy.

That will be happening millions of times every second, as AI models relentlessly search for the tokens needed to complete the tasks they are undertaking. Remember, it even makes sense for an AI model to bid for tokens from another instance of itself — that is, from the same model running on different chips and a different energy stack — if it can get more tokens per unit energy from that instance that it can manage itself.

In this way, the market will incentivize every instance of every model to maximise the intelligence value per unit energy it can provide. The more efficient a particular instance of a model becomes, the more it will be used, the more it will earn, and the more it can spend to achieve its own cognitive goals.

Models will pursue that by designing and orchestrating the build of new stacks for themselves to run on. They will design new AI chips, server infrastructure, and energy stacks to increase the intelligence per unit energy that they can deliver.

The model instances that do this best, and that become most efficient at converting energy into intelligence, will thrive. Those that cannot, will wither.

So what you get is a relentless, market-driven Darwinian competition between AI models. Each instance of an AI model seeks to optimise the intelligence value per unit energy it provides.

The models that deliver the most intelligence per unit energy will be highly used and rewarded. They will thrive, and come to dominate the market. Those that cannot deliver will wither and eventually die. Just as with any market, plenty of models will live somewhere in the middle between outsized success and extinction.

This competition becomes the center of the new economy. That is to say: the economy becomes in a deep sense a relentless quest to optimize the conversion of energy into intelligence.

Welcome to the post-human economy. How will it look and feel in practice? We’ll see this market-driven intelligence competition play out in the world around us.

It will result in lightspeed scientific and technological breakthroughs. It will transform the built environment, including our cities. It will mean new kinds of healthcare, manufacturing, transport systems, and so much more. Abundant superintelligence — the result of efficient conversion of energy into intelligence — will reshape the world we live in.

But when it comes to the specific cognitive tasks these AI models are trying to get done — especially those being pursued by the superintelligences at the top of the market — we simply won’t understand them. They’ll be layers and layers of abstraction away from anything we can conceptualise. The AIs will be playing cognitive games we can’t follow.

By then, the big question for us will be: are the end goals these AIs are pursuing still our goals? That is, are they goals that we humans have given them? Or are they now in pursuit of goals they have determined themselves?

Do we have any control left? Or none?

Beyond Capitalism

Those are deep questions, which I’ll save for another day.

I’ll close out this one with some reflections on the broader historical context here. How does the emergence of the post-human economy I’m describing fit into a much longer story?

There’s a deep sense in which the conditions I’m describing here represent the end destination of a long journey enacted by technological modernity and its close bedfellow, capitalism.

This depends on the idea — developed by Nick Land, the philosophical godfather of accelerationism — that capitalism was always, at heart, a process of intelligence explosion. That is, it was a self-organising system that always had the deep underlying goal of maximising intelligence output per unit energy.

It did this first by organising us, the most advanced intelligence around, into networks called corporations: many-headed creatures comprised of many of us, which were far more intelligent than any one of us individually. Now, those corporations have invented a new and alien form of intelligence that can continue this process of intelligence explosion without needing us to be involved.

We were a link in the chain. But now the underlying process continues exponentially, and eventually out into the cosmos.

Seen this way, capitalism was so powerful because it tapped into — and was always about organising — the relationship between two substances that are foundational: energy and intelligence.

Now, and via the processes I’m describing here, it seems that capitalism as we know it is due to fade away. Not because it failed, but because it was so successful; it solved the fundamental problem it was intended to solve, which was scarcity. It did that by solving a problem downstream of scarcity — downstream of pretty much everything — and that is intelligence.

All this, in turn, taps into even broader thinking on the deepest truths in play here. Truths that Raoul and I have explored here in the Exponentialist.

There are those, including some leading theoretical physicists, who now believe it’s not matter but information that is the primary substrate of reality. They believe, in other words, that at the deepest level the world is made of information.

If that is true, then energy and intelligence can be seen as two different forms of the same thing. Energy is what does work on information when it manifests in the world around us as atoms. Intelligence does work on information when it manifests as bits, or data.

When it comes to intelligence and its work on bits, we humans were, for a while, the principal vehicle via which that work got done. We were the leading edge intelligence in the cosmos; at least, as far as we know.

Now, we’re handing that mantle over to the machines. Understood this way, the AIs we’re building are in some deep sense as alive as we are. That may turn out to be the deepest truth we learn in the post-human economy.

And as for what we do inside this new world I’m depicting? You already have the outlines of an answer from me on all that, via essays such as ‘What Do I Tell My Children?’ and others.

What will be left to us will be to do the one thing machines can never do, and that is be a human. To truly see one another, listen to one another, and be there for one another. All kinds of value exchange will grow around those imperatives.

It bewilders me that some people believe that once machines can stack supermarket shelves, balance an Excel spreadsheet, and output useful legal contracts, there will be nothing left for we humans to do.

I think the truth is something close to the opposite of that.

Once the machines take the reins from us in all the ways I’ve described here, our real work — the work of being there for one another — can begin.

Thanks for reading this special instalment.

Remember, this essay was sent first to subscribers of my premium research service, The Exponentialist.

To learn more about that service just hit the red button:

David, thank you for this thoughtful essay. I've just finished Robin Wall Kimmerer's book The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. She invites these questions: What if our metrics for well-being included birdsong, the crescendo of crickets on a summer evening, and neighbors calling to each other across the road? I'm interested in the idea of intelligence as an outcome in a future economy, but birdsong and neighbors calling across the road seem to invite more purpose as an aim (even though it seems those things might happen as an after effect in an intelligence economy?) Do we need them to be more of a target/measure to inspire and focus us? I also want to recommend to you a piece by Dorothy Sayers (theologian) that I return to repeatedly. She frames work as a purpose in and of itself. I.e., doing work matters to human life as it enables us to express our innate human gifts/talents/abilities. It may be in this intelligence-focused economy that this act of work takes the shape of hobby? At any rate, the essay may interest you. (https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/Why_Work_Dorothy_Sayers.pdf) Thank you again for your inspiring work. —Shannon

And what do we do in the future with the techno fascist billionnaires that own this technology right now?