New Week #139

The humanoids are coming

Welcome to this update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 25,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

This week, a cluster of news stories had me reflecting on the coming rise of the humanoid robot.

Back in the Lookout to 2024 in January I said that this year would prove a breakout one for humanoids. And so it seems to be proving.

This week, I want to take a closer look. What’s happening? And, more important, what is the deeper context here? Why does the humanoid story matter, and where is it heading next?

*

First, the stories that caught my eye. There have been so many developments, but here’s just a glimpse:

A major player, US startup Figure, this week released a preview of its next humanoid, the Figure 02:

The Figure 01 humanoid is already at work inside a massive BMW factory in Spartanburg, South Carolina. And it’s not the only humanoid already out in the field; Agility’s Digit robot is at work inside a select number of Amazon fulfilment centres.

Meanwhile, German robotics startup Neura showcased its general-purpose humanoid 4NE-1. Neura take aim, in this video, at the dream that is a everyday household helper robot:

I’m a father of two chronically untidy 10-year-old boys. A humanoid that can pick up Lego, serve breakfast, and load the dishwasher would have been so great. Alas, while it seems such a robot is coming, it won’t come soon enough for The Chaos Years in my household.

Neura’s update was timed to coincide with a major announcement on humanoids from Nvidia. The superstar chip company is launching a suite of platforms and tools to supercharge the development of these robots.

That includes Isaac Lab, a simulation platform that allows for the humanoid training at lightspeed. And GR00T, an AI foundational model for humanoids that can take a range of inputs — natural language, video footage, teleoperation by a human — and via those develop the outputs that will cause a specific humanoid to perform the desired complex task.

Progress, then, is accelerating. It feels as though humanoids are approaching a LLM-style breakthrough moment.

But what’s the deeper context here? Why does this matter? The answers lie in deeper underlying demographic truths.

*

Lots of people want to think in structured ways about the medium and long term future. But their thinking is often marked by the same species of mistake. That is, they tend to get hung up on shiny new technologies, and neglect the human context against which those technologies will play out.

Out world is shaped by deep structural trends in human behaviour and mindset. Demographic trends are perhaps the deepest and most powerful of them all.

We’ve touched in this newsletter on the demographic reality that we’re heading towards, and what it means for GDP growth.

GDP = Population Size + Productivity. Now, population growth is flatlining, and that’s a disaster for economic growth.

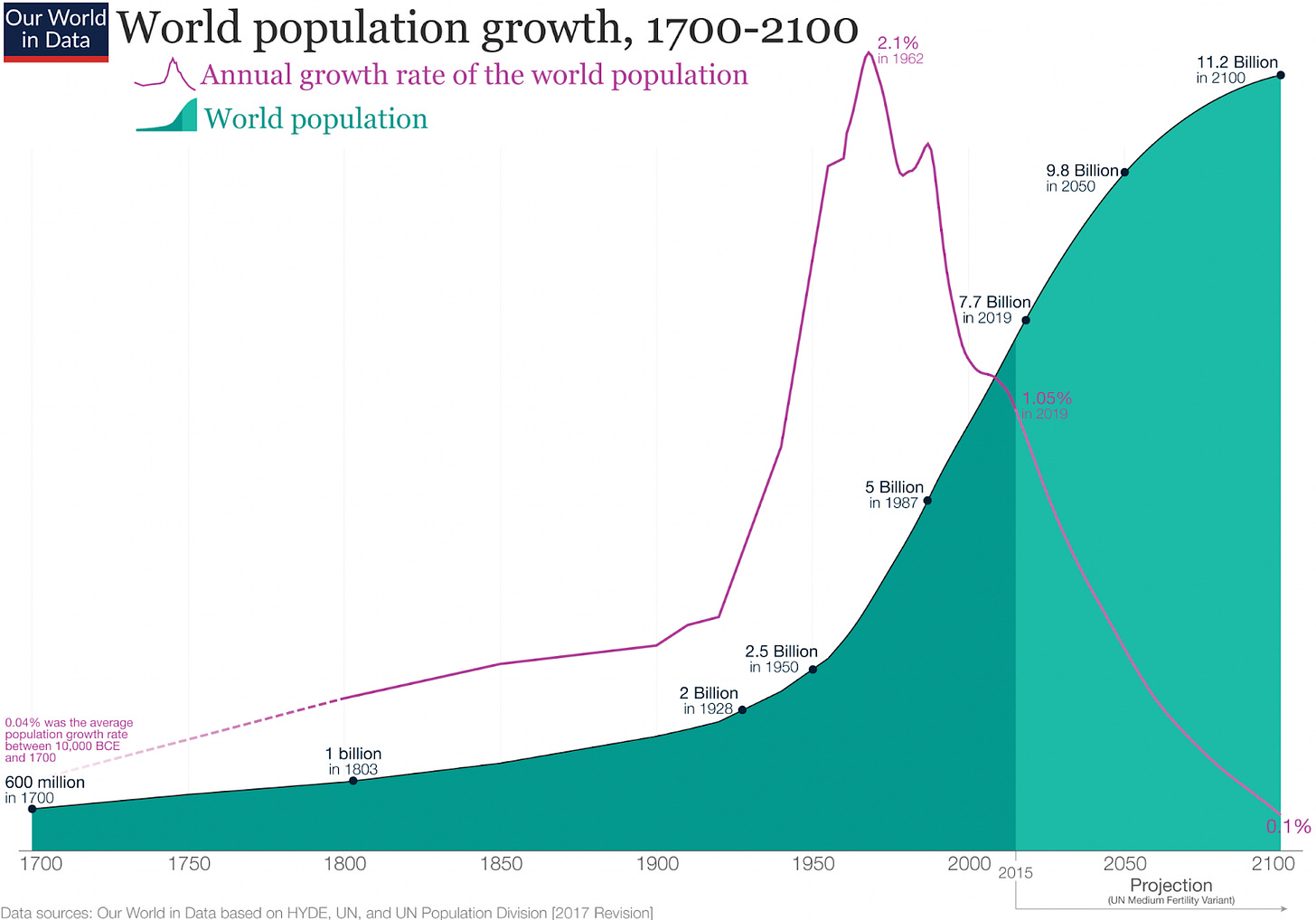

For 2023, UN data has the global population growth rate at 0.9%. As you can see, the UN now forecasts that global population will peak at around 10.4 billion in the 2080s and then start to decline:

Almost all the population growth between now and then will come in the developed world, principally in Africa and India.

In the developed nations, growth is already flatlining. These populations are getting older, fast. That’s creating societies of a kind we’ve never seen before, in which the centre of gravity is with the very old.

Working age populations are in steep decline across Europe, China, and Japan:

According to China’s National Bureau, people ages 16 to 59 accounted for 61.3% of the mainland population last year, down from 62% in 2022.

Even in the US, where the situation is a little better, UN forecasts have working age population growth bumping along near zero for rest of century:

None of this is news. But a new study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and published in the Lancet in March shows it’s all happening even faster than anyone expected.

A fertility rate that keeps population constant — the ‘replacement rate’ — is 2.1 children per woman. The US is at 1.6; China is at 1.2. The UN World Population Prospects has previously said the global fertility rate will dip below replacement level around 2056. But this new study says that date will come way earlier, in 2030.

Professor Christopher Murray of the University of Washington led the study; he is one of the world’s leading demographers. He says of the result: ‘That's a pretty big thing; most of the world is transitioning into natural population decline. I think it's incredibly hard to think this through and recognise how big a thing this is; it's extraordinary, we'll have to reorganise societies.’

And all of this has one giant implication: labour shortages. The decades ahead will be shaped by a quest to find an answer to that challenge.

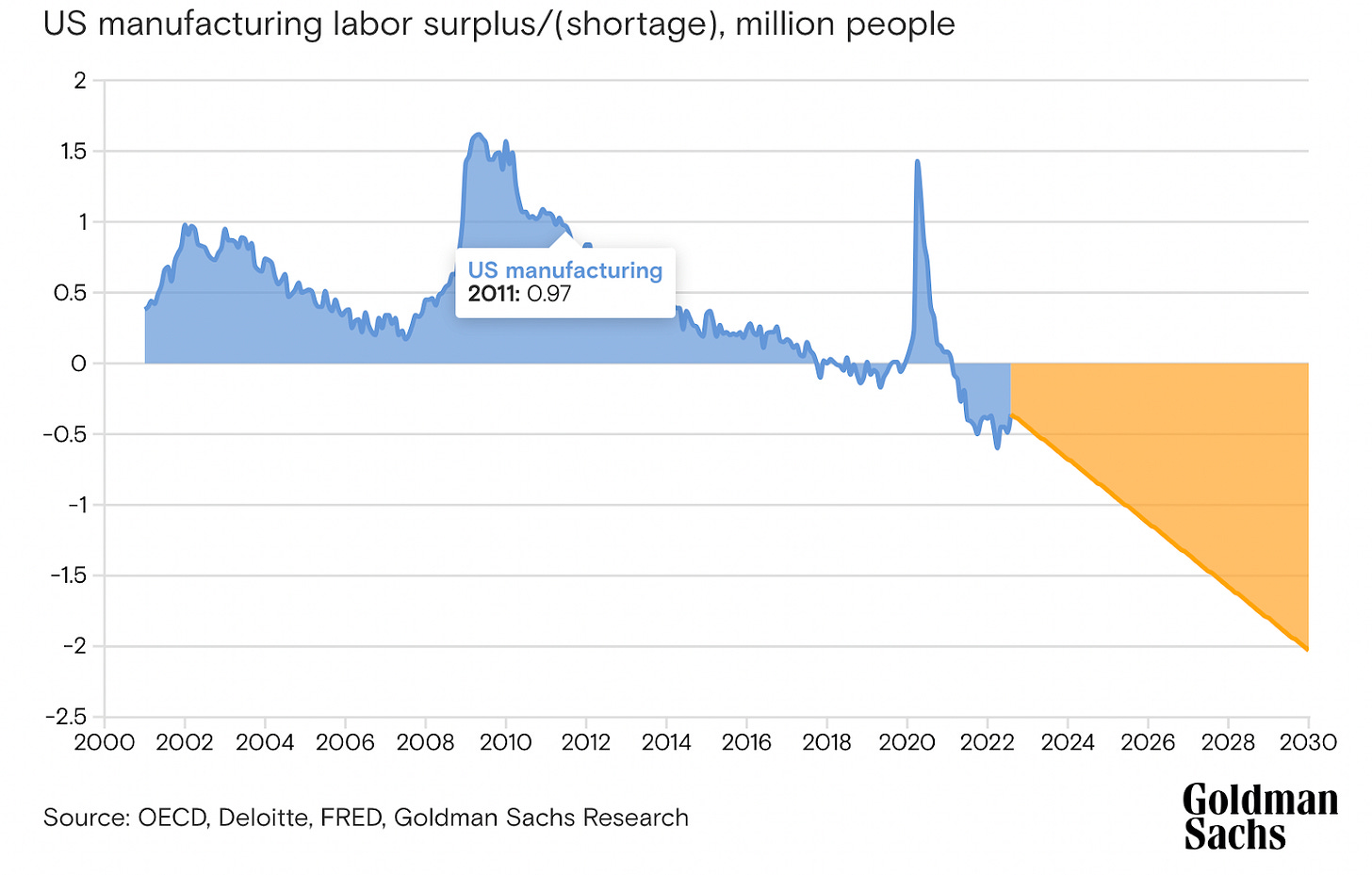

Since the pandemic there’s been much discussion of a structural labour shortage in the US, and disagreement on whether it’s real or an illusion. The US Chamber of Commerce says the US is still missing 1.7 million Americans from the workforce when set against February 2020.

And if there isn’t a structural shortage now, then one sure is coming. Here’s a forecast for US manufacturing from a recent Goldman report. It has the manufacturing sector short by 2 million workers in 2030.

What does all this mean?

Barring a miracle or Armageddon event — in which case all bets are off anyway — population growth in developed nations isn’t coming back. The big consequence? If we’re to avoid an unravelling GDP, we can only look to the productivity side of the equation. And that means technology. This puts the Exponential Age journey with tech at the heart of everything.

That story is so deep. AI agents will do all kinds of knowledge work, and I’ll be writing more about that soon. But there’s also a stupendously broad subset of work that boils down to physical tasks, and that means robots.

When it comes to physical work, we’ll need an army of mechanical labourers to do much of it for us. The stage is set for a robot explosion.

It needs to happen. And now, it’s what we’re going to get.

*

Humanoids have come a long way in the last 12 months. But reality check: there’s a long way to go before they’re roaming free around factories, fulfilment centres, and homes.

Sure, Digit is inside Amazon and Figure 01 is at BMW. But they’re working in a small and highly structured environment, performing relatively simple rote tasks. The dream is a humanoid that can be as flexible and unsupervised as a person.

Still, in a way that wasn’t the case even 24 months ago there’s little doubt: the humanoids are coming. And that truth is driving statements such as this one, from iconic VC Vinod Khosla:

Elon Musk is in no doubt about the transformational impacts set to play out:

‘I think Tesla Optimus has the potential to be more significant than the vehicle business over time. If you think about the economy, the foundation of the economy is labour. Capital equipment is distilled labour. So, what happens if you don’t actually have a labour shortage? I’m not sure what an economy even means at that point.’

The questions that come next are deep, and strange.

Via a combination of machine intelligence and humanoid robots, are we humans set to be crowded out of the workforce altogether? If there’s little work for people to do, how do they earn a living? What new purpose will they find? What does the world look like when companies staffed by AI serve other companies staffed by AI? As Musk asks, what does the economy even mean in those circumstances?

For my part, I hope that the rise of machine labourers will liberate us to find new social and economic settlements. That means new and more meaningful ways of serving, being with, and truly seeing one another. Let machines do the work that machines can do, so that we can do what only humans can do.

Meanwhile, the trajectory we’re on with AI and robots builds the case for the idea that, at some point, some form of universal basic income will be needed. UBI is one of those ideas that causes fierce divisions of opinion. I see it as a way of distributing the gains that will be generated via our shared technology legacy; a legacy that belongs to all of us.

But even if we can get to that place eventually — and that’s a big if — history suggests socio-economic transformation of this scale won’t come without a mighty and painful convulsion. If there is a path to the UBI-fuelled good life, it won’t be an easy one.

We’re only at the start of all this. No one knows for sure how it will all play out.

But I’ll keep watching and and working to make sense of it all in these postcards from the new world.

See you next week,

David.

“Via a combination of machine intelligence and humanoid robots, are we humans set to be crowded out of the workforce altogether? If there’s little work for people to do, how do they earn a living? What new purpose will they find?”

Important questions. Here is another one: Who will own the operating systems on which the humanoids run--operating systems which will surely be managed centrally?

Meaning, for instance, a government might be able to remotely gain control of locally owned humanoids in order to put down a local protest or manage civil unrest.

Political and economic elites will continue to exist in the future, just as they do now, and a massive population of centrally controlled AI-bots can create some unpleasant and unintended consequences for a democracy.

I don't buy we need humanoid robots anymore than I buy that the future of aeronautics is planes with flapping wings.

"But their thinking is often marked by the same species of mistake" is exactly that point. Emphasis on species. We have AI scientists talking about artificial superhuman intelligence as if it has to exactly mimic and pass through humans - even with all our flaws, violence, irrational fears, fragile egos. Is it built for purpose or for the flattery of imitation and all the limitations that brings? Less time taking selfies, more time looking forward, please.

And while I am no degrowther, I'm not seeing robot armies as saviors for GDP standards. As if that's what's most worth saving for humanity.

No pearl clutching to "God Save the GDP" here. Ever-increasing GDP as a purpose unto itself remains a Ponzi scheme, an old utopian capitalist promise of infinite exponential growth free from undesirable side-effects or trade-offs. It's arguably making our world less inhabitable by the day.

Grossly ignoring the systemic limits of all that growth, and the crutch of power-sucking robots made from boundless mineral extraction from the earth, pretends like none of that is actually happening in our hermetically sealed vacuum. We need to challenge ourselves more on our out-of-date models and ideas.