New Week #136

Jobs, productivity, and the AI J-curve

Welcome to this update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 25,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

To Begin

My eye was caught, this week, by compelling evidence on generative AI and a changing labour market.

We’re all hearing so much about the coming impact of AI on jobs. There’s real anxiety — even fear — over what lies ahead. When I speak about AI to professionals inside knowledge work organisations, the most common question I’m asked is: what do I tell my children?

So in this instalment I stick to one subject, and go a little deeper than usual. Deep, that is, on AI, the future of work, and the likely shape and implications of an AI-fuelled productivity boom.

It’s a chance to think aloud about several different threads that I’ll continue to try to pull together. Let’s get into it.

🧑💻 AI, the J-Curve, and the Future of Work

This week, new research allows us a glimpse of the coming collision between AI and knowledge work.

A new paper from Harvard Business School says that since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, demand for freelance writers, coders, and app developers has declined by 21%.

The study, Who is AI Replacing? — The Impact of Generative AI on Online Freelancing Platforms, saw researchers looked at 2 million job postings on freelancing hubs such as Upwork and Fiverr. They discovered significant decline in demand for tasks vulnerable to automation via LLMs. The researchers said image generation tools such as DALL-E are also changing the labour market; they found a 17% decline in demand for tasks associated with image generation, such as graphic design.

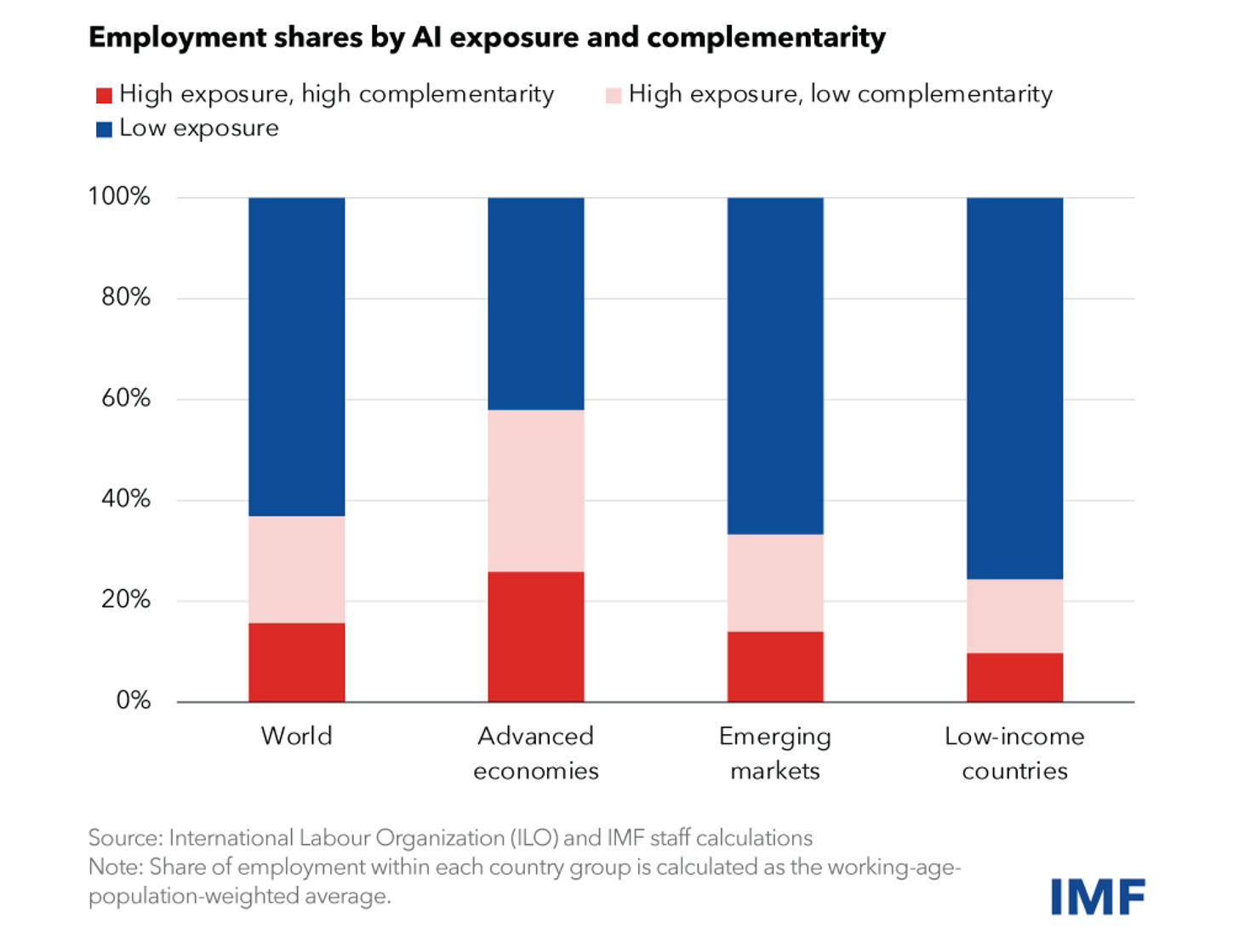

Meanwhile, this week the IMF said the generative AI revolution could spark massive labour disruptions and spiralling inequality across the Global North. A new report urged governments to take measures that will ameliorate the social impact, including improved unemployment benefits for those shunted out of jobs.

In January the IMF said generative AI will impact 40% of jobs worldwide. Some of those jobs will be automated away, they said, while for others the use of AI will become a key aspect of the role.

Another glimpse of the AI-fuelled future of work this week?

Japanese telecoms giant Softbank have developed ‘emotion cancelling’ AI for use in call centres; the technology makes angry callers sound calm and reasonable.

AI as a filter on emotional expression? It’s the dystopian future none of us have always dreamed about.

⚡ NWSH Take:

Large organisations, from Accenture, to HSBC, to Salesforce and far beyond, are working hard to figure out how best to leverage AI both internally and to enhance what they offer customers. When it comes to my consulting, grappling with this challenge is currently all anyone wants to talk to me about.

It’s impossible to believe that, medium-term, this won’t have a profound impact on jobs. A huge shock is ahead when it comes work and the role it plays in the societies of the Global North.

AI agents are going to do lots of the tasks currently performed by knowledge workers. Put that together with displacement of physical labour via robots, and you have the makings of what my Exponentialist partner Raoul Pal calls ‘a deflationary nuclear bomb’ soon to fall on our economies.

The robots are coming fast, by the way. Elon Musk was in Cannes this week, promising a $20,000 Optimus humanoid that will cook dinner, play the piano, and staff factories the world over. We all know that Musk’s timelines tend towards the optimistic. But directionally, I think, he’ll be proven right.

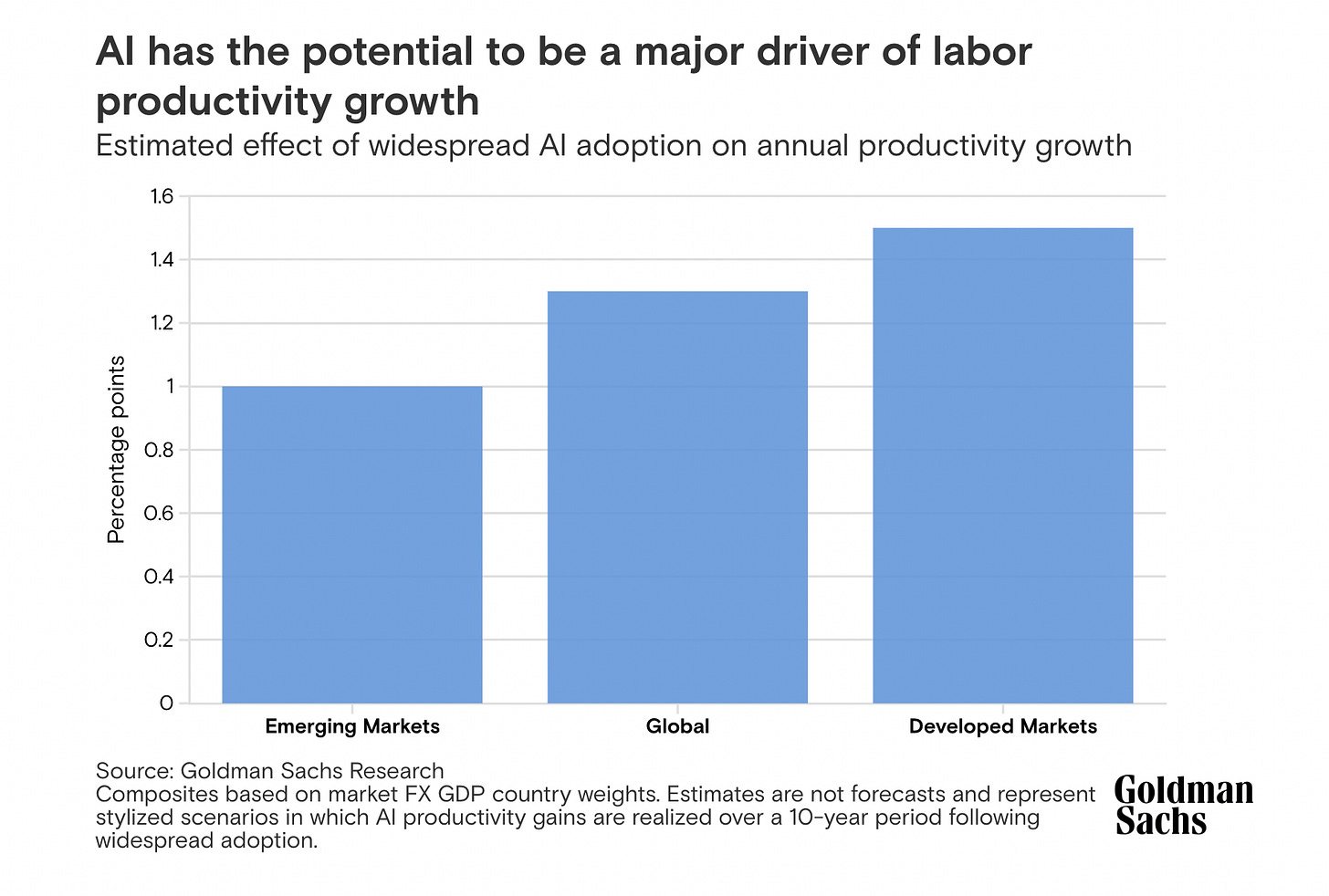

Right now some are pouring cold water on this AI moment by pointing out that we’re yet to see any meaningful impact on productivity numbers.

But look at the history of new technologies and that criticism soon loses its potency.

It’s true enough, at the moment, that generative AI has not delivered a measurable productivity jolt. But we’ve seen this before with the advent of PCs, and with pretty much every new general purpose technology from the steam engine to electricity: there is a lag between deployment and productivity impact.

MIT professor and automation expert Erik Brynjolfsson has, famously, gone deep on all this. His conclusion? The cause of the lag we saw with PCs — at the time it was called the ‘productivity paradox’ — occurred while organisations developed the new skills, habits, and human systems needed to use them.

Brynjolfsson developed what he calls the productivity J-curve theory to describe this phenomenon.

The J-curve tells us that when a new technology is deployed, new skills and habits must evolve around it. The development of those skills is not captured in any productivity measurement, so for a while there’s no visible productivity boost. Indeed, there can be a measured productivity dip as time and energy are poured into creating these new organisational capabilities. But eventually the organisation develops the new skills and norms it needs to use the new tech, and productivity soars.

In other words, technologies can evolve and even be deployed rapidly, but people — and especially people in groups — tend to move at the speed of human.

Right now, we’re riding the J-curve with AI. Large knowledge work organisations are still very much in the what the hell do we do with this, and how do we persuade Bob in accounts that he should care stage of figuring it all out.

It makes sense, too, that we see a significant impact on the freelance job market — reflected in the new Harvard Business School study — before we see anything comparable inside large organisations.

It’s far easier for solo professionals to weave AI through their work. Professionals inside large organisations are caught in a tangled web of workflows, relationships, and habits. They can’t simply start executing a task in an entirely new way without coordinating this with many others, and typically without permission from the top. And even if they do leverage, say, ChatGPT to become more productive, unless others around them become more productive too — more able to handle the larger number of outputs being produced by our hypothetical AI adopter — then there will be no overall organisational productivity gain.

In other words, integrating this technology into the workflows of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of staff is hard, complex, and messy. It will take time. We’re still closer to the beginning of that than the end.

But it will happen. It’s just a case of riding the J-curve. Every new technology platform is a unique case, of course, so it’s hard to say how long the ride will take. Brynjolfsson sees an AI-fuelled productivity boom coming across the next few years to two decades, and says special characteristics of generative AI — including the ability to interact with it using natural language — may accelerate the ride through the J-curve.

Goldman Sachs have done a lot of work on all this; they say there are ‘very positive early signs’ that AI will eventually boost productivity. But they don’t expect that to start showing in the productivity numbers until 2027.

In the meantime, the technology is becoming more powerful and accessible by the month. Microsoft this week made available their new Copilot Plus PCs, which are augmented by powerful AI assistance.

The point I’m driving at here?

Huge structural forces are pushing us to quest after an AI-fuelled productivity miracle. But it will come with a serving of social disruption.

The economies of the Global North desperately need AI and robots to offset their falling working age populations. A new report from the OECD this week said birth rates in rich countries have fallen to record lows, and that this is set to ‘change face of societies’.

Population growth isn’t coming back any time soon in the Global North. The only hope we have of keeping GDP growth alive — and of growing out of our enormous debts — is via technology.

But deep job displacement will be the price we pay. Everyday knowledge workers and those engaged in physical work are going to be shunted aside in the hundreds of millions, and most likely towards more precarious working lives. The fruits of growth will flow overwhelmingly to the owners of capital; the owners, that is, of the AIs and robots.

So what to do?

AI godfather Geoffrey Hinton is clear: last month he revealed that he has advised the UK government to offer a universal basic income to offset the impact of AI on jobs.

‘We have no plans to introduce a universal basic income,’ said the UK government.

Well, quite. No government has a realistic plan here. In fact, none of them are even talking about it. Soon we’ll enter full campaign season for the US presidential election. How much will we hear about the AI revolution from Biden and Trump? My guess is almost nothing at all.

But this will be, surely, the last presidential election in which simply not talking about AI is an option for either candidate. Across the term of the next president the social impacts of job displacement will become impossible to ignore. Reordering our societies around the transformations associated with intelligent machines will become the big topic for our politics. This will push ideas now considered radical — including UBI — into mainstream discourse.

These are the kinds of conditions that fuel the arrival of new social and political arrangements. Factories and mass production shaped the formation of the job as we know it now, and, in turn, so much about the way we organise our collective lives.

What will the arrival of intelligent machines do to our current dispensation? I’ll keep watching.

We Can Work It Out

Thanks for reading this week.

The coming impact of AI on our working lives is a classic case of new world, same humans.

I’ll keep watching, and working to make sense of it all. And there’s one thing you can do to help: share!

Now you’ve reached the end of this week’s instalment, why not forward the email to someone who’d also enjoy it? Or share it across one of your social networks, with a note on why you found it valuable. Remember: the larger and more diverse the NWSH community becomes, the better for all of us.

See you next week with another postcard from the new world. Until then, be well,

David.