Learning to Be Human

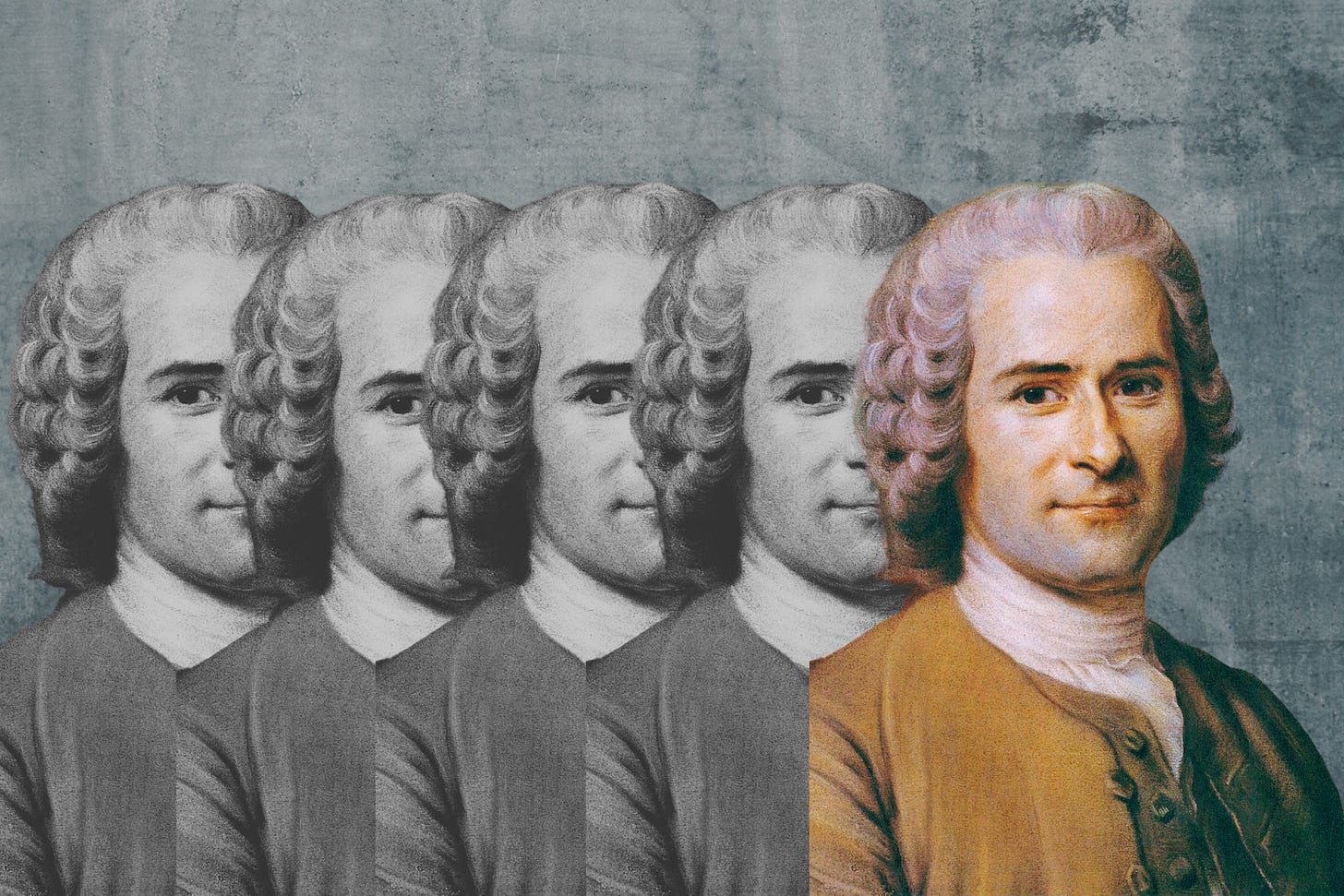

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the age of superintelligence

Welcome to this update from New World Same Humans, a newsletter on trends, technology, and society by David Mattin.

If you’re reading this and haven’t yet subscribed, join 30,000+ curious souls on a journey to build a better future 🚀🔮

Over the Christmas break I wrote a long essay on AI and education for Global Macro Investor.

My research for that essay sent me back to the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. And particularly to his famous treatise on education: Emile

Rousseau wrote Emile in 1762, just as modernity was heaving into life. The printing press was remaking culture. Rapid urbanisation was underway: his adopted city of Paris was growing fast and would soon reach 600,000 people. Early commercial capitalism was taking hold; the city was becoming a world of freely trading artisans, merchants, and hustlers serving a newly-emerging consumer class. And the culture was in a deep state of flux, too. Ancient sources of wisdom — primarily that meant the Bible and adjacent religious texts — were being challenged by the new power of the scientific method.

The old rules were being shattered. Everything seemed up for grabs. No one knew where the vast technological and economic forces being unleashed might take humanity.

Sound familiar?

Rousseau watched it all. And he brought it all to bear on his thinking about education.

His deepest concern wasn’t classroom tactics. It was, rather, around a set of deeper questions. What does it mean to be a human being inside this version of modernity? What gifts does technological change give us, and what shadow costs does it impose? How do we shape people able to remain authentically free, and authentically human, in the fullest sense?

These are exactly the questions we face now, as intelligent machines arrive.

To answer these questions, Rousseau invented the idea of childhood. That is, the idea that childhood is a legitimate lifestage in its own right, with both its own imperatives and profound consequences for the rest of life. And he criticised the way children were prematurely forced into adult modes of thinking. It was wrong, he said to force-feed children facts, abstract principles, and rational techniques before they’d had a chance to ground any of it in lived experience. The result was a hollow parody of real thought. Children educated in this way, he said, performed a kind of empty ventriloquism, repeating correct answers without understanding them.

AI vastly accelerates our capacity to make this mistake.

It outputs a constant stream of fluent explanations, frameworks, and answers. The danger is that we immerse children in these outputs before they can make sense of them. They might remember the answers. They might get good at generating similar ones. But we’ll be creating the appearance of thought rather than the reality.

My instinct: for the youngest children, minimal AI. We don’t want them locked onto screens in dialogue with unhuman forms of intelligence. We want them talking to each other and to human teachers. Learning to attend. Learning to listen. Learning to see themselves as sites of rational and creative judgement.

This reminds me of the attitude that Steve Jobs famously took to his own inventions when it came to children. When asked how his children liked the iPad, he explained that they hadn’t used one. We don’t really spend time at home using those devices, he said. We talk to one another about art and history.

As for older children, the current conversation about AI and education tends to revolve around tactical questions. How do we stop students using AI to do their homework? How do we teach them to use AI tools, and which ones? How do we prepare them for the jobs that will be left once AI eats most knowledge work? Will there be any jobs left?

These questions matter. But they are downstream of deeper and more important ones. The kind Rousseau wanted to answer. What kind of society do we want to forge? What is the difference between knowledge and wisdom? What does it mean to be a whole human being?

Rousseau’s greatest insight was the realisation that any meaningful thinking on education is always downstream of an underlying theory of the human. Before we can answer how to educate, we must answer: what kind of human beings are we trying to create?

Via the rise of intelligent machines — machines that seem to be colonising territory we once thought belonged only to we humans — we now face that question anew. And it’s becoming urgent. As intelligent machines enter the picture, we must ask: what is a human being? How do we remain authentically free amid the conditions that are emerging now?

Rousseau’s gift to us is the insight that education is the operating system for humanity inside conditions of civilisational rupture. What we need now is nothing less than a rethinking of human ways of living and being in an age of intelligent machines. An account of what remains distinctly ours when superintelligence arrives. An articulation of what about we humans is worth preserving, and why.

In other words, to figure out education, we must first figure out us. Let’s get to work.

This was #19 in the series Postcards from the New World, from NWSH.